Abram's Flocks

In the first place we must be clear about the class of nomad to which the patriarchs belonged. It would be an anachronism to liken them to the nomads of the great Arabian desert who appear to have been camel breeders; these were tireless caravaneers and, usually, resolute brigands. This was a truculent, almost epic form of nomadism, on the grand scale and entirely amoral. It had nothing in common with the quiet, peaceful, almost bourgeois (one belonging to the middle class) form of nomadism adopted by Abram the shepherd and his descendants.In ethnological terms these wandering Bedouin, like Abram, are known as breeders of smaller livestock. With their sheep and goats they camped either on the grassy steppes on the edge of the cultivated land (as we saw occurred in Sumeria) or on the natural pasture as yet belonging to no one (as we have just observed in Canaan, their new dwelling-place). Once the grass in one place had been grazed they left for other pasture land, which had, of course, to possess a well or a spring where men and beasts could quench their thirst. Before long the shepherds had established a kind of regular circuit, always going from the same oasis to the same piece of pasture, from the water source to the same valleys. They came thus to have established routes over the length of which they considered, in accordance with the unwritten law of the nomads, that they possessed grazing rights.

'Breeders of smaller livestock': this expression seems automatically to exclude the ruminants, cows and oxen, which would be unable to bear the long journeys under semi-desert conditions -three days without drinking, which means nothing to sheep or goats. And yet the Scriptures mentions the calves and bulls which Abram offered to YAHWEH. How is this to be explained?

It has just been pointed out that Abram's clan, which had grown to some importance on leaving Egypt, had arranged the routes for its flocks, so that they were regularly moved at fixed dates to different places with periodical returns to watering-places. Near each of these wells they took care to set up guard posts to prevent brigands from destroying their equipment, and on occasion these sentries were entrusted with the care of a few cows and calves. Thus the cattle could graze the scanty grass of the neighbourhood near the drinking place, and with the help of a small store of hay laid up during the good season they managed to eke out an existence. This is the explanation of the allusions in the Scriptures to the calves and bulls belonging to a group of nomads. It meant that there was a fixed establishment, though of a rudimentary kind, separate from the clan which, always on the move, could, after all, obtain on occasion a few head of cattle.

The existence of the small farm also enabled the occupants to sow and harvest some cereals although, generally speaking, pasture land and corn land are different in character, but this primitive arrangement should not be regarded as showing any tendency to a settled agricultural way of life, in the proper sense of the term. Life was still organized on a nomadic and pastoral basis; the planting of fruit trees alone constitutes the sign of man's definitive settlement on the land.

Your servants are shepherds, like our fathers before us (Bereshith 47:3). They were shepherds, raising and looking after smaller livestock, by which was meant sheep and goats.

Abram's sheep

Abram's sheep and those of the Hebrews at the time of the patriarchs were probably oves laticaudatae (widetailed sheep) a kind which can still be seen in Palestine.

Certain passages of Bereshith and Vayiqra inform us of the characteristics of this caudal appendix which contained a large proportion of fat. More precise information still on the subject of this animal of the land of Canaan is furnished by the historian Herodotus and the naturalist Aristotle: the tail, which was extremely fatty, was made up of adipose tissue capable of providing the body with water during those periods when the beast could not be taken to a drinking-place. It is a huge and rather inelegant organ which may weigh anything up to about twenty pounds.

These sheep's tails provide the Bedouin with a dish of which they are very fond; it is cut in slices and fried. Sheep or ram's tail, down the ages, was often brought to the altar of YAHWEH to be offered as a sacrificial gift. The fat from these tails was also used in cooking and provided the oil for lamps.

Abram's sheep were rarely completely black though few again were entirely white. Rather were they pied, that is, a mixture of black and white; on the fully grown animals the coat assumed a faded appearance which, with the advance of age, became increasingly general.

It is difficult to obtain an exact idea of the numbers in Abram's flocks. The Scriptures gives us to understand that when he left Egypt he owned a considerable number, but no figure is mentioned. Nowadays, the westerner who visits the Near East is often astonished at the huge flocks to be encountered in Transjordania. Does that mean that Abram, the owner of much livestock was a great meat eater? Not at all. The sheep was raised, principally at least, for the production of wool. Its coat was used, in the first place, to provide the raw material for the clothes of the shepherds and their families. The women were spinning and weaving all the time. The same material was used to make tents. In addition, wool was the basis of the trade established between the nomad and the citizens of the land of Canaan. Thus bales of wool were bartered for sacks of corn, manufactured articles, and also bars of gold and silver which were carefully stored under the tents. Sheep, as the producers of wealth, were hardly ever used for meat. Obviously in certain circumstances one was offered in sacrifice to YAHWEH, but for these gifts to YAHWEH the shepherd usually preferred to take a ram or a Iamb (a male, of course). It is only in La Fontaine's fables that a countryman kills the hen which lays the golden eggs.

In fact the patriarchs' diet was basically one of milk (of sheep or goat) and cereals (bought from the farmers of the country). It required some special event which interrupted the daily routine, the arrival of a guest, for example, even an unknown one, for the chief to give the order to kill one or several head of livestock.

The flock was there not to provide meat but wool. Thus among these tribes of shepherds in charge of many thousands of sheep, the great popular celebration was always, and everywhere, the sheep-shearing.

Can we mention wethers in this context? The Law expressly forbade the offering on the altar of any animal which had undergone castration. You are not to do that in your country says Vayiqra (22:24). Was it merely the offering of a castrated animal which was thus forbidden? Or was it the fact of mutilation? Josephus, the Jewish historian, enables us to say that it was the second, for he tells us that castration of animals was strictly prohibited in Yisrael (Antiquities of the Jews, IV, 8, 40). Probably this prohibition with regard to domestic animals was suggested by the horror with which the Yisraelites regarded human castration. Thus there can be no question of wethers in speaking of the flocks of the shepherds of Yisrael.

Abram's goats

In addition to sheep there were the goats. On the long marches for change of pasture as well as on the pasture land itself and at the drinking places, both kinds of animals were herded together, without disadvantage. According to the characteristic details furnished by the Scriptures the goats of the Hebrew nomads were probably of the kind known as Capra membrica, easily recognizable by its well-developed horns, by its height and chiefly by its drooping ears. It was black in colour, as was mentioned above, and the poet without forcing the image excessively, could speak of the hair of the beloved, hanging down her neck, as like a flock of goats frisking down the slopes of Gilead (Shir Hashirim 4:1).

The coat of these Canaanite goats was made up of two sorts of hair. On top was a rather rough long fleece which was used especially for tent cloth. Beneath there was finer hair which, although short, was soft and woolly. The spinners valued the goat particularly, and also the cooks, for goats' milk was especially good and even in the time of the patriarchs cheese was made. Goat kid, too, furnished a tasty dish on occasion.

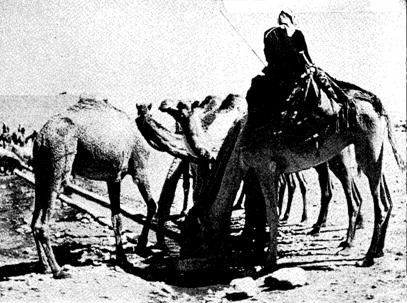

Did Abram Have camels?

It is difficult to speak with equal certainty about the camel, and it is not even certain whether the camel had yet been domesticated.

When he left Egypt and the Nile delta Abram had become, we know, a wealthy shepherd, the owner of many flocks and of fine ingots of precious metals. Among his animals the Scriptures mentions the camel. Archaeologists have objected that this animal is not represented on the monuments of the Pharaohs until a much later period. But the camel might have already been employed in the usual way on the semi-desert fringes of the Nile delta; and Abram's camp was confined precisely to this frontier region. There seems, therefore, no reason why it should not be granted that the Hebrew clan, which had lately grown wealthy, might have possessed a certain number of dromedaries (camels with one hump).

At the time of Isaac's marriage, when it was a question of providing him with a bride, Abram, who at that time had established his camp in southern Palestine, sent his slave, Eliezer, with some camels, to Haran on the Upper Euphrates, the 'land of his kinsfolk'. This long journey, nearly a thousand miles there and back, required camels if it was to be done in reasonable time, but mention of camels may have been an anachronism.

The shepherds must have led a dreadful life. To provide the flocks with enough grass the different pastures had to be at some distance from each other. The man in charge of the flocks was obliged to live in isolation. He had always to be on the alert, on the look-out for an animal which wandered away, a ewe dropping a Iamb, a Iamb that was sick. The shepherd was responsible for his sheep; he had to defend them against thieves and also against wild beasts, of which there were many, always on the watch for prey. There were wolves, much feared at that period, and lions which found refuge in the impenetrable woods bordering the Yordan.

The dogs used were a mongrel breed of jackal, about the size of a wolf-hound, very fierce and hardly domesticated, trained to attack wild beasts. These dogs did not fear to try conclusions even with a lion. Their function was one of protection rather than of watching that the flock did not stray.

Watering the flocks

Every evening the shepherd led his flock from the pasture to the drinking place, usually made up of wooden troughs or clay cisterns arranged near the well. The curb, as we have seen, was nothing like those to be found in the European countryside. It was very wide, anything from about four and a half to nine feet in diameter. It was practically at ground level with a low wall to prevent the animals falling into the water. The well at Beersheba, dug by Abram, which since those remote times has hardly been modified in its general form, shows how the walls have been worn by the cords used in pulling up the skins or vessels. When camp was struck the well was covered over by wide slabs of stone, and over these a thin layer of earth was spread in order to render the spot invisible to the Bedouin brigands who were always bent on destruction out of sheer malice. If the opening of the well was smaller than usual it was always covered during the day by a heavy stone which, in the evening, was moved away on the arrival of the flocks.

The flocks came to the well in closely packed ranks. The shepherds kept them at a distance, as the animals went to the troughs in turn and on the order of their own shepherd; the different flocks could not be allowed to mix without causing disputes and quarrels. It was each shepherd's task, of course, to draw the water and fill up the troughs for his own flock. This was very hard work indeed. Life as a shepherd was really very arduous and exhausting.

At the end of the day -the drinking trough.

You are here: Home > History > Abraham Love By YAHWEH > current