HARAN: YAHWEH SPEAKS TO ABRAM

The Characteristics of A Clan

The Clan of Terah

Abram was accompanied by his wife, Sarai, who was his half-sister; she was, in

fact, Terah's daughter but not

In relation to all the members of the clan, its head usually possessed discretionary power. He could judge and reprove; if necessary he could even order the death of his children, his grandchildren and his relatives. He was also free to sell them as slaves. That was the unwritten law of the desert. At the time of Abram, the patriarch reigned as a master over his own people. Evidence of this is to be found when, under the most tragic circumstances, we see Abram about to make a ritual sacrifice of his son Yitschaq.

The wife, and on occasions, the wives (for polygamy, without being obligatory,

was freely allowed), were the property of the husband, who, moreover, in the

day-today language of the family was called

ba'al, that is, the master. The wife, taken prisoner in war or purchased,

had little say in the family organization of the ancient

On summer evenings in the tent, the head of the clan, with the men squatting around him, would recite the genealogy of the former patriarchs. It was a long list, often embellished with anecdotes, historical feats, and important events, which were thus handed down from generation to generation in a set form which soon became unchangeable. It is easy to understand how this oral tradition came to possess a very marked character of authenticity.

Does this mean that all the clans of the same tribe were descendants of the same ancestor? The Semites held this to be the case. In reality, from time to time each of these primitive clans were joined by other small groups encountered by chance in their wanderings on the steppes. Both parties weighed the advantages of joining forces. Then a very simple symbolic ceremony took place: the two chiefs, as representatives of the two clans, opened a vein of their arms and exchanged blood; and so the strangers became an integral part of the large family, they were now of the same blood as all the natural descendants of the ancestors.

Henceforward, the members of an ethnic group (at the simplest stage a clan, at the most developed stage, a tribe) regarded themselves as members of one body. An insult to one of them became an offence experienced by all. If the blood of an individual member of the clan or tribe was shed, the report spread at once among the shepherds belonging to the same family group and the cry went up 'our blood has been shed !' And so it can be understood how these men of the steppes were inspired by a collective feeling of vengeance, or 'vendetta'.

The sons and grandsons of the patriarch, the wives and concubines of the chief, the servants of the wives, and the tribal elements artificially associated by the rite of exchange of blood all formed the various constituent elements of the clan. To these must be added the servants and the slaves.

Physical appearance of Abram's clan

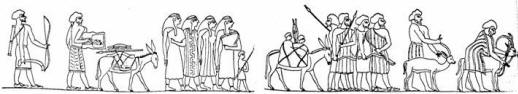

This wall-painting at Beni-hasan (the modern name of the village in which the tomb of Chnumhotep was discovered) can be dated with certainty; in a corner of the picture an Egyptian is brandishing a sheet of papyrus giving all the necessary information about the period in which this mural was painted. It was the sixth year of Pharaoh Sesostris II (twelfth dynasty), that is the year 1901 (or 1898, according to certain authors) B.C.

If we accept the date of 1850 for the adult age of Abram, the work of art in question would therefore be scarcely fifty years earlier than what is known as the religious period of the patriarch. Within a few years, it could be contemporary with his youth. These Amorites, pictured at Beni-hasan, belonged to a branch which was a neighbour of the one to which Abram belonged. Both Amorites and Arameans for long led a similar pastoral existence; it is well known that this kind of life on the steppes stamps an individual in the same way as living in a settled community does.

A closer examination of this work reveals the sheik at the head of the

procession, and the hieroglyphs give his name as Chief Ibsha (a genuine Semitic

name). His finely chiselled features are characteristic of his race. His thick

black hair is trimmed to cover his head like a cap and his almond-shaped eye,

sparkling with malice and intelligence, peers out under a prominent brow. His

upper lip is shaven, but a fine beard traces a thin line along his jaw, coming

to a small elegant point beneath his chin. Ibsha and his companions are dressed

in clothes of various kinds: some of them, the torso bare, wear a fairly long

loin-cloth reaching from the waist to the knees; the men-at-arms, with their

lances and bows, wear robes

With a resolute air the women, clad in multi-coloured tunics, push forward in a group. They are well-built, sturdy matrons, with large busts, admirably suited for motherhood. Beautiful black hair falls down to their shoulders and in pigtails over their chests. According to this wall-painting, therefore, we have clear evidence that in Abram's time the women were not veiled; we see them here, their faces free to the air with no fear of showing themselves. This enables us to observe how the Semitic type is more marked in the female sex: large, beautiful eyes but also a more pronounced nose, a certain heaviness of features and a general appearance of plumpness. The Egyptian artists, who could seize on the slightest picturesque detail with no attempt at caricature, have put on record a series of accurate sketches.

An inscription informs us of the trade of these foreigners: 'arrival of the

black paint for the eyes brought by the thirty-seven Asiatics'. It refers, in

fact, to cosmetics intended for the women of the valley of the Nile. The Semites

whom we see here could not, therefore, be regarded merely as shepherds;

nonetheless, they were nomads living, like all the shepherds of Terah and

Thus, with no forcing of words and taking care not to exceed the rights of a

commentator on a work of art, we may well believe that the wall-painting at

Beni-hasan provides us with a very close idea of the physical appearance of

Terah's small nomadic clan.

Wall painting from Beni-hasan

Abram and his family must have looked like this group of

Bedouins

.

You are here: Home > History > Abraham Love By YAHWEH > current