Abram Reasons for the departure

Terah made them leave Ur of the Chaldaeans to go to the land of Canaan (Bereshith 11:31). Why did they leave? Bereshith offers no explanation. But there is no reason why we should not endeavour to discover the motive for this decision whose suddenness is foreshadowed by nothing in the Scriptural text.

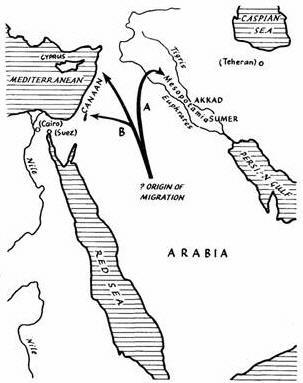

In about 3000 B.C.

(a) A wave of warrior shepherds, coming from northern Arabia, settled in

Mesopotamia (Akkadians).

(b) A second wave, from the same region, settled on the Mediterranean coast

(the Amorites).

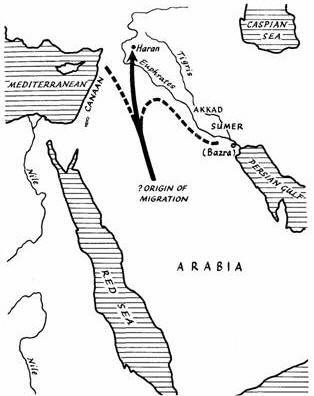

THE FIVE SEMITIC INVASIONS About 2500 B.C.

(c) A second wave of Semitic shepherds, again from northern Arabia (the Arameans), settled in the Upper Euphrates and spread its small clans throughout the region (Abram). Later, in about 2000 B.C., these Arameans founded the kingdom of Damascus.

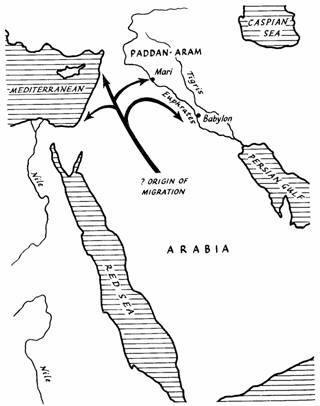

THE FIVE SEMITIC INVASIONS

(d) A fourth wave of Semitic invaders -the Amorites, also from Arabia -fell upon the Near East: in the west they attacked Canaan, in the north Paddan-aram (Mari), in the east Babylon.

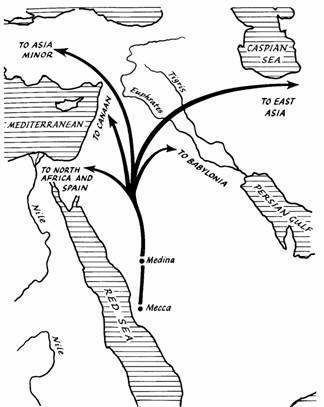

THE FIVE SEMITIC INVASIONS

(e) In the seventh and eighth centuries of our era there occurred the great invasion of the Mohammedan hordes who rapidly spread over the whole of the Near East, western Asia, North Africa and southern France (where Charles Martel brought them to a halt in 732).

No 'spiritual' reason for this departure

At Ur all the circumstances appear to be confined to the sphere of human affairs; Terah's departure with his family seems to be explained by psychological or historical reasons from which YAHWEH's intervention, expressed in a visible manner at least, seems to be excluded. Nevertheless, some authors hesitate to accept the rational explanation, basing their opinion on two passages of the Scriptures.The first of these texts is to be found in a later chapter of Bereshith (15:7). It shows us Abram, settled at that time in the region of Hebron (the southern part of the land of Canaan), where he had just pitched his tents. YAHWEH, who had already appeared to him on three occasions (at Haran, Shechem and Bethel) revealed to him on that day the future of his descendants, and in conclusion reminded him of certain features of the recent past: 'I am Yahweh who brought you out of Ur of the Chaldeans to make you heir to this land.'

Man may argue that for YAHWEH to have 'brought them out does not mean that on this occasion HE did so by personal, visible and authoritative manifestation. It seems easier for them to suppose that YAHWEH, the ruler of all men and all things, prompted Terah, the head of the family, by the operation of normal reasoning or even by a subconscious impulse, to make ready for his departure. In any case, it can be clearly stated that both Terah and his son Abram were led by the existence of Yahweh before leaving Ur. They saw worship of the gods of the Sumerian pantheon; of this they furnish us with clear proof. Both Terah and Abram chose the northern city of Haran as the objective of their lengthy migration. The two nomads, before leaving the lower Euphrates, were influenced by the revelation and orders of Yahweh which makes it difficult for secular men to understand their movements.

The second text which causes a certain difficulty to some commentators occurs in the Acts of the Apostles. This passage describes the appearance of Stephen, the first Messianic martyr, before the high kohen and the Sanhedrin, who were to condemn him. In putting forward his defense Stephen declared that the YAHWEH of honour appeared to our father Abraham, when he was in Mesopotamia, before he lived in Haran, and said to him, 'Depart from your land and from your kindred and go into the land which I will show you.' Then he departed from the land of the Chaldeans and lived in Haran (Acts 7: 2, 3).

Before the Jewish tribunal which, he was well aware, was shortly to sentence him to be stoned as a 'blasphemer', Stephen spoke as an advocate, a confessor of the faith and a zealous preacher. He cannot be blamed for not speaking as a careful historian. He was recounting an event which happened nearly two thousand years beforehand. We must not hold him too closely to an interpretation which is possibly the echo of a late Jewish tradition.

In conclusion, it appears that there is no need to invoke a supernatural explanation for this departure. At Ur YAHWEH gave clear express orders. Men look, rather, to psychological and historical reasons.

The real motive for departure

The real motive for departure is furnished by history in general and social history in particular. Terah's family lived during the social confusion of Sumeria on its conquest by Akkad at the beginning of the nineteenth century B.C., so something must be said to begin with about the political situation of the southern region of Mesopotamia. The third dynasty of Ur, whose advanced civilization had shone brilliantly, had just fallen in 1955 B.C. to the onslaught of a Semitic conqueror who established the capital of his kingdom at Isin. Now at Larsa, some ninety miles distant, there was a rival dynasty (also Semitic) rising threateningly against the sovereign of Isin. These two States were at war for two hundred years (1955-1755); sometimes the cities of the former Sumeria depended on Larsa, sometimes they gave obedience to Isin. For this reason the long period is called by orientalists the Isin-Larsa period. In passing it may be noted that the youth and departure of Abram occurred during this troubled period of prolonged hostilities.Thus the Semites proved the uncontested masters of Mesopotamia. Logically the clan of Terah, encamped near Ur, should have been perfectly satisfied with this political situation, since they were among men of their own stock.

In fact, settled residents, whether city-dwellers or farmers, have little liking for nomads on the fringe of a well established State organization. From inscriptions on clay bricks we know that the inhabitants of the cities referred to these perpetual wanderers as 'brigands and cut-throats' and other similar names.

Disliked by all (including their own race, as we have seen), deemed undesirable by the governments (even Semitic governments) and cordially hated by the established population, these wandering shepherds themselves decided to leave the inhospitable lands of the kingdoms of Babylon. They knew where they were to go, as the Scriptures tells us: Terah made them leave Ur. ..to go to the land of Canaan. Why did they go there? It was because they knew that vast open spaces were to be found in this Mediterranean land near the other end of the Fertile Crescent. The grass there was sufficient for their flocks, there were few cities, and they could wander untroubled. At the time of Abram the regions at the south of Canaan were under the dominion of Egypt, a remote sovereignty, very gentle and almost slack in operation. In Babylon, Terah and all the Aramean shepherds, his brothers, had to bear the rule of a totalitarian, theocratic State, whereas to the south-west of the Yordan there was, it seemed, a country ruled by an easy-going government. There would be no more scribes with their figures and statistics, no more tax collectors! There was complete freedom to wander and an ideal isolation. Terah and his people, retiring like all nomads, chose freedom.

Cuneiform tablets, the result of excavations in Babylon, reveal by implication at least that the departure of Terah's clan must not be considered as an isolated historical event. Throughout the whole of the first half of the second millennium there was a general exodus of these Aramean shepherds towards the north-west. Some groups went to settle in the region that is now called Syria. Others migrated to Transjordania (to the east of Yardan and the Dead Sea), or again to Canaan (now Palestine). Some clans even pressed on to the eastern borders of the Nile delta where the Egyptian officials granted them permission to settle on the fringes of the cultivated land and the desert. It was a departure en masse, the great Aramean migration.

You are here: Home > History > Abraham Love By YAHWEH > current