Yoseph's Brothers Cruel Sequel

Not content with having sold their brother, Yacob's sons did not hesitate to cause their father the most grievous affliction. Perhaps they thought to take secret revenge for his marked preference for Yoseph. They took the coat, given to Yoseph by his father, and dipped it in the blood of a goat killed for the purpose. Then with feigned sorrow they brought it to their father. 'Examine it' they said, 'and see whether or not it is your son's coat.' Yacob, on one occasion tricked his father; in his turn he was now tricked by his own sons. When he saw the fine cloth torn and stained the old man had no difficulty in reconstructing the scene: 'A wild beast has devoured him,' he exclaimed, 'Yoseph has been the prey of some animal and has been torn to pieces!'

There was nothing very surprising about this. It was one of the occupational hazards in the hard life of the Semitic shepherds who had to defend themselves night and day against the attacks of wild beasts which were always on the watch to fall upon a sheep which strayed even a short way from the rest of the flock. One of the most dangerous of the wild animals was the lion which could easily find a lair in the thorny thickets of the valley of the Jordan. The Old Covenant mentions lions something like one hundred and thirty times, which gives us some idea of the fear they caused to the shepherds; lions disappeared from the Holy Land at the time of the crusades when they were exterminated by the knights who had come to fight the Saracens. There were also leopards, constantly on the prowl whose rapidity of movement was proverbial. Wolves, too, could sometimes prove formidable opponents and the bear, also, or rather the female bear at the time when she was suckling her young. There were many and incessant dangers facing the shepherds on the plains.

Confronted with the blood-stained coat, which told its own story, Yacob could abandon any hope of seeing his beloved son alive. He thus tore his clothes (for the purpose of making himself unrecognizable to the spirit of the dead youth, which by definition was dreaded and dangerous). Then he put on the well-known saq (described at length in the preceding volume devoted to Abraham, in the chapter concerning Sarah's funeral); this, it will be remembered, was a kind of loin cloth of rough material or very coarse leather which was tied round the waist.

Yacob then received the condolences of his daughters and, rather revoltingly, of his sons, the authors of the crime. But Yacob refused to be comforted: 'No,' he said, “I will go down in mourning to Sheol!” What exactly did he mean by that?

At first sight it might be thought that in his affliction Yacob had decided to wear the saq, the garment of mourning, until his death. Something has already been said here about Sheol, but to elucidate Yacob's remark it should be added that in the subterranean dwelling where the 'shades' of the dead were gathered, the dead person's 'double' continued to live a diminished existence, rather like the Egyptian ka; and in this dark and sombre place the dead person retained the appearance and even the clothes of the moment of death For example, at the time of the Kings, when the ghost of Samuel was conjured up by a necromancer, the old 'judge of Yisrael' was wrapped in the cloak which he had been wearing at the time of his death (1 Sam. 28: 14). In Sheol monarchs retained the insignia of their high office, old men could be recognized by their white hair, the warrior who had died fighting still showed the marks of his wounds. Thus, in the present case, Yacob desired to lead the slower-paced life in Sheol wearing the garments symbolizing his despair. And his father wept for him.

Meanwhile the young man who was officially dead arrived safe and sound in Egypt with the merchants' caravan; there he was at once sold as a slave to Potiphar one of Pharaoh's officials and commander of the guard

The Political State Of Egypt At The Time Of Yoseph

(About 1650-1600)

As a general rule the Egyptians of antiquity were opposed to foreigners. In the ports of the Delta or of the Red Sea, and at the frontier posts on land, foreign merchant) bringing products or raw materials needed for Pharaoh's court, for the temples or the workshops, were readily welcomed. If in some cases it was necessary to allow foreigners to establish trading posts the Egyptian officials took care to assign them a definite city as a residence, where they were confined to special quarters from which they were forbidden to leave. Whether they were Libyans from the west, Canaanites from the east or Nubians from the south all these foreigners were invariably regarded with marked distrust by the Egyptians.

Now in the part of the story with which we are shortly to be concerned we shall discover Yoseph the Hebrew quickly attaining the highest imaginable honours in Egypt: the young shepherd, the son of Yacob, a Canaanite shepherd, was not long in becoming the vizier, the first minister of the powerful sovereign. He was to be invested with the highest office after that of the monarch himself, receiving the title of viceroy. Bereshith gives a careful description of Yoseph's investiture (Egyptologists agree as to its accuracy): Pharaoh took the ring from his own finger and put it on Yoseph's as a sign of his trust in him, and placed a heavy gold chain round his neck.

This story of a Semite achieving high office at the Egyptian court appears difficult to accept: the castes were kept so entirely separate, and in high government circles there was a very marked antipathy for everything foreign. Asiatics, Canaanites particularly, were heartily disliked and no secret was made of it. In these circumstances Yoseph's extraordinary Egyptian adventure as told in Bereshith, the rapid rise of an unimportant Hebrew to a high position in Pharaoh's court, might well, it seems, have been invented for reasons of prestige. And on this score an argument has been advanced against the authenticity of the story.

An argument advanced against the authenticity of the story

As it happens history sheds a certain light on this chapter of Bereshith. In Yoseph's time (which can be dated approximately between 1650 and 1600 B.C.) Egypt was no longer in the hands of native rulers. Already for one hundred and fifty years, perhaps even for two centuries, lower Egypt had endured the harsh occupation of peoples of largely Asiatic origin, called by the Egyptians the Hyksos (or shepherd kings, but this translation is uncertain). In these circumstances it is historically if not geographically inaccurate to say simply that Yoseph was extraordinarily successful 'in Egypt'. For although he did build up a large fortune in the land of Egypt that country was then occupied, militarily and socially, by Asiatic invaders, who at that time were masters of the country and its destiny. Knowledge of this fact helps us to understand better how with the help of these Asiatics and for their own benefit, Yoseph, racially closely related to them, managed to attain almost to royal status.

Thus Yoseph's adventure is seen to be wholly acceptable, indeed it fits in neatly with the historical context; we have an occupying power when the opportunity occurs making use in its administrative plans of a man of its own country of origin.

There is no need here to go back over the long and turbulent history of the Hyksos which in many ways, indeed, is rather obscure. But since Yoseph's rise to power occurred within the framework of the Hyksos occupation of Egypt and can only be explained by it the following rapid historical summary will help to make matters clear.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century B.C. the Hyksos invaded the Near East in formidable waves, suddenly appearing from various regions of Asia. It is probable that this human tide was set in motion under the pressure of Indo-Aryan tribes which attacked Media. This was the cause of great upheaval among all the peoples who were more or less settled in the north and the north-east of Mesopotamia. Events were complicated by the fact that, as these hordes advanced, some of the ethnical groups unsettled by all this disturbance joined the invaders, who after overrunning Mesopotamia advanced on Canaan and fell like a swarm of locusts on the rich land of Egypt.

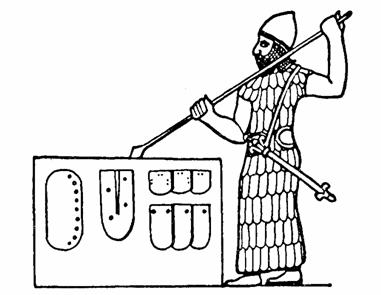

The victory of the invading hordes can be explained by their use of new arms against which the Egyptian soldiers had no defense. These warriors from remote parts of Asia used chariots drawn by horses, an animal at that time unknown in the Near East. We may well imagine the surprise and the terror caused by the appearance on a battle field of this weapon which broke through the infantry lines, opened breaches in the marching columns and fell unexpectedly on the rear of the enemy. In addition the Hyksos possessed considerable superiority in arms over the Egyptians. The latter began their attacks with a primitive form of bow provided with arrows made of ebony-tipped reeds; for hand to hand fighting they used copper battle-axes, clubs and daggers; even at the time of the Middle Empire (2000-1800 B.C.) they were still at the stage of wooden swords which had been hardened in the fire. The arms of the Hyksos were very different. They used a powerful bow made of several layers of flexible wood, strengthened with horn; their arrow heads were metal and therefore sharp. To protect his body the warrior wore a kind of tunic very like the coat of mail of the medieval knights, that is, a leather garment on which were sewn plates of copper. Lastly, the Hyksos' sword was made of bronze, in the form of a two-edged scimitar which could be used with both hands at once. It is hard to see how the Egyptian army with the arms at its disposal could have withstood these well-armed hordes.

The Jewish historian Yosephus (A.D. 37-92), referring to the historian Manetho (third century B.C.), quotes a few sentences from the latter (whose works have been: lost) to give us an idea of the brutality of this Hyksos invasion. 'I hardly know how the wrath of YAHWEH,' explains Manetho, 'was unleashed upon us, and without warning a people of unknown race, coming from the East, had the effrontery to invade our country. On account of their strength they seized it without striking a blow' [a slight I exaggeration: it would be more accurate to say that they entirely overran the Egyptian defenses] 'seized our leaders, burnt down the cities, razed the temples of the gods to the ground and treated the natives with this greatest cruelty, massacring some of them, and carrying off the children and women as slaves....' Without necessarily taking the Hyksos' side it must be acknowledged that they followed the military law of the times, the same law applied by the Egyptians in their victorious expeditions beyond the Nile valley.

The actual result of all this was that these Indo-Aryans, surrounded by a mixture of different peoples who had followed them and served as auxiliaries, settled with evident satisfaction in Egypt. Despite their brutality as soldiers the Hyksos cannot be regarded as primitive or as barbarians, at any rate so far as the governing classes were concerned. The newcomers to Egypt possessed. sufficient perception and intelligence to recognize quite clearly that the civilization with which they had so roughly come into contact was superior to their own. After their extraordinary success, therefore, they set about adopting the customs of the Egyptians, they copied their art and endeavoured to carry on their traditions so far as possible. They did their best to become Egyptians. In imitation of their predecessors several of the Hyksos sovereigns adopted the title of Pharaoh.

Huyan, one of the Hyksos princes, went on to establish a vast empire which extended to the north-east as far as the Tigris and in the south included Egypt as its boundary. Avaris his capital was established in Egypt. Archaeologists have discovered a seal bearing his name with the proud title 'Master of the country'. Thus in the northern sector of the course of the Nile the Hyksos were established, taking the place of the national dynasty which they had just overthrown, adopting the religion and customs of the invaded country and soon passing themselves off as real Egyptians.

Such were the conditions in the country when Yoseph arrived there, and was sold to a new master, probably an Asiatic. Yoseph was incorporated into this Asiatic civilization established as the occupying power in the Delta. It is important for these matters to be made clear, otherwise the whole story of Yoseph and his sudden rise to power would seem hardly credible.

Armour consists of metal plates sewn onto a garment made of skin.

Yoseph Index Yoseph Sitemap Scripture History Through the Ages Yoseph Egyptian Adventure Yoseph Scriptures and Dreams The Plot Against Yoseph Yoseph's Brothers Cruel Seqel Yoseph In The House Of Potiphar Yoseph In Prison Pharaoh's Strange Dreams Yoseph Slave Becomes Viceroy Of Egypt Yoseph's Unexpected Family Reunion The Ten Brothers Before Yoseph Yacob Goes To Egypt Yoseph and the Death Of Yacob YAHWEH's Sword History Further Anxieties Of Yoseph's Brothers Yisraelites Remain In Egypt Period Of The Great Persecution