The Plot Against Yoseph

Yacob, who remained at his headquarters at Hebron, sent the greater part of his smaller livestock (sheep and goats) to the pastures of Shechem; it seems certain, therefore, that for his fifty qesitah the patriarch had acquired unquestionable rights of pasture in this region. Of course, another portion of his flocks continued to graze neighbouring plains of the Negeb. Under the supervision of the ten brothers a considerable number of sheep and goats had been moved to the valley of Shechem. A patriarch as careful of his interests as Yacob likes to be informed regularly of the state of his flocks; for this purpose he decided to send his young son Yoseph to Shechem for news.

On arrival at the place where he could have expected to find his brothers Yoseph could see no one. A man, belonging to the neighbourhood told him where they were: 'Your brothers have moved on from here; indeed I heard them say, "Let us go to Dothan"'. Dothan is a small place situated some twenty miles to the north, now known as Tel Dotan. The present village stands on an artificial hillock formed by the debris of the various buildings which down the centuries have fallen into ruin on, top of each other. From a height of nearly a hundred feet. it dominates a plain (Sahel' Arrabeh) watered by springs and a wandering stream. The countryside has retainer] its pleasant character: there are orchards of oranges and lemons, fig trees, grassland. In many places there are water tanks hewn out of the limestone. We can be fairly certain that it was in this pastoral setting that Yacob's sons had set up their tents when Yoseph came to find them.

From a distance they saw their young brother, who was easy to recognize because of his long coat. 'Here comes the man of dreams,' they said one to another 'Come on, let us kill him,' one of them suggested. 'We can say that a wild beast devoured him,' added a third, 'then we shall see what becomes of his dreams.' Reuben, the eldest, intervened. His behaviour towards his father had not always been blameless and possibly he had no desire to have another crime on his conscience. We must not take his life,' he said. 'Shed no blood, throw him into this well in the wilderness, but do not lay violent hands on him.' Reuben hoped to save Yoseph’s life and return him one day safe and sound to his father. A few lines further on (Bereshith 37:26) we are told that it was Yahudah who was responsible for the measures to save Yoseph's life.4

The water tanks were hewn out of the rock and in the rainy season were filled by various methods from the water in the neighbourhood. Thus in a watertight tank the precious liquid was kept for those months when the sun dried up the springs and wells. These tanks must not be confused with the bathing-pools, also common in Canaan, which were open to the sky. The usual form of water tank was bottle shaped. There was a small narrow opening, like the neck of a bottle (to lessen the risk of pollution) giving access to a chamber, round or square, generally of medium size, but the side could be as much as one hundred feet long. The opening was carefully closed with a stone (like the wells in the wilderness) or with logs of wood. In these tanks water kept very fresh and was safe from evaporation. The wandering shepherds often took care to flatten the ground all round the openings so that they alone could recognize the presence of this underground reservoir on which, at least at certain times of the year, depended the lives of their flocks.

Frequently in the history of Yisrael we find abandoned water tanks used as places of refuge, especially at the time of the Philistine invasions. Sometimes they were transformed into prisons (YermeYah 36:6-13). Into one of these dismal and dark places (the precaution was certainly taken of stopping up the opening) the unfortunate Yoseph was unceremoniously thrown.

4 The Kohenly code (P) whose documentary materials are used here from time to notice numerous and perceptible inconsistencies in the narrative This is explained by the fact that the scribe who, in about the sixth century B.C., wrote down the text of the Pentateuch which we now have, made use of various traditions (they are also termed cycles, sources or codes) which he reverently collected and faithfully recorded with the eagerness of an archivist. It should be remembered that these 'cycles' were preserved for five centuries. In oral form at the time of the nomads they were recited fervently by the story-tellers) and a beginning was made in writing them down about the time of David (about 1000 BC) It was the chapters of these traditions, differing on occasion in detail, which were transcribed by the scribe in the sixth century.

The following are the characteristics of the three cycles whose presence It is possible to discern in the account of the life of Yoseph:

The Yahwistic cycle (or J, because God is designated by the name YAHWEH). It is in a popular, brisk, narrative style. The Elohistic cycle (or E, thus called because God is designated by the name Elohim).

The Kohenly code (P) whose documentary materials are used here from time to time in the enumeration of the genealogies YAHWEH is called by the name EI Shaddai (the Rock?)

The sixth-century scribe respected his texts to a great degree, and endeavoured to collect together as much as possible of the ancient cycles; he partially recopied them, placing them side by side even if they recorded the same events in different ways. Thus in the dramatic anecdote which has just been related, which comes from the E cycle. it is Reuben who prevents the brothers from killing Yoseph, and the latter is to be sold shortly afterwards to a caravan of Midianite merchants; whereas in the J cycle he proposes instead to sell Yoseph to a caravan of Ishmaelites These differences of detail will not surprise the reader if he knows the reason for the variations. The use of these traditions endows the Pentateuch with an indisputable stamp of authenticity. It can be seen that the author of the final draft took every possible precaution to go back to the most authoritative source material, and we cannot blame him for not having made use of the latest methods of work of historical science It remains true nonetheless that his blunders constitute an undeniable proof of his honesty as an historian.

Time for sheep-shearing. A lot of work, but afterwards tremendous public rejoicing.

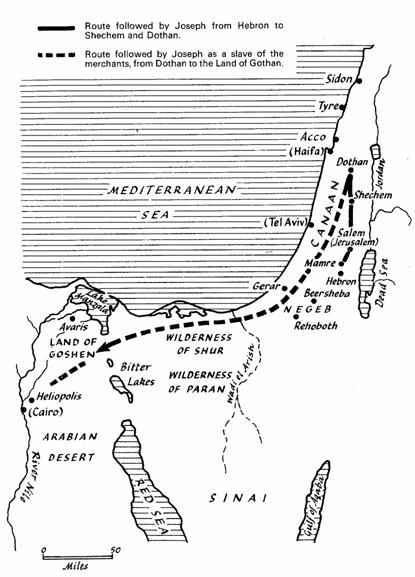

YOSEPH'S ROUTE FROM HEBRON TO DOTHAN, DOTHAN TO EGYPT

Yoseph Sold By His Brothers

After this exploit the brothers sat down to eat. They had hardly finished their meal when they saw a group of merchants with camels on their way down to Egypt. They hailed the merchants and for twenty pieces of silver the bargain was concluded: Yoseph was taken from his dark prison and the merchants led him away to be a slave in Egypt.

These merchants, we are told, were Ishmaelites (J cycle) and, a few lines farther down, Midianites (E cycle). The non-specialist reader might well think that this divergence is of little importance. It is nonetheless interesting to note that at the time of the patriarchs the export of spices, gathered and processed in the eastern countries and destined for Egypt, was almost exclusively in the hands of Ishmaelite and Midianite merchants.

The question of the camels is more difficult, Some scholars have stated that the camel was only domesticated towards the end of the twelfth century B.C. thus a good five hundred years after the time of Yoseph, and they point out that Egyptian monuments show no representations of camels before this date. This theory is disproved by the recent discovery of silhouettes of camels dating from the predynastic period (before the year 3000). We know from other sources that the camel was used in Arabia in the fifth, or at least the fourth millennium, but it did not make its appearance in the Near East until a much later period. In Egypt the ground was too slippery for camels, but they were probably adopted at an early date by the patriarchs and used by them even when they were traveling with their flocks on the plains of Canaan. On his return from his journey to Egypt Abraham went back to Hebron with camels. Later on he sent his confidential slave to Haran to find a wife of Aramean blood for his son Yitschaq and the journey there and back was performed on the back of a camel. So there is probably no anachronism here.

Another historical detail which gives the account an undeniably authentic character is the list of the various spices carried by the caravan which, we are told, was coming from Gilead: Their camels were laden with gum tragacanth, balsam and resin, which they were taking down into Egypt. Gum tragacanth is a form of resinous substance gathered from the bushes of the species Astragalus; it was used by the ancients as an astringent remedy. Sere, the Hebrew name of the product which is translated by balsam, was gathered and prepared in the Canaanite region of Gilead. Now the passage of Bereshith takes care to tell us that the merchants to whom Yoseph was sold came in fact from Gilead. From other sources we know that the Egyptians were heavy buyers of this balsam which was applied to wounds.

The resin referred to flows from the trunk or even from the branches of a kind of rose-tree extensively cultivated in Canaan. The Egyptians burned this sweet-smelling substance in the temples and also in private houses. It was also used in the manufacture of certain cosmetics; it was applied to certain parts of the body to relieve pain and was also used to prevent the hair turning gray or falling out. All these typically Canaanite products, archaeology has discovered, were very popular in the Egyptian markets.

We have by no means come to an end of the historical proofs which seem to proliferate on every page and which help to authenticate the facts of the narrative. Thus we are told by the writers, whose account was based on ancient sources of dependable authenticity, that the brothers sold Yoseph to the Ishmaelites who took him to Egypt. This was no chance occurrence. Asia, and more especially Canaan, was regarded by the Egyptians as the source of the best slaves; for this reason men of the regions that are now Palestine and Syria fetched the highest prices on the market. Sometimes, and already by the time of the Middle Empire (2000-1800), a Canaanite was designated in Egypt by the name of aam, that is, slave. The Midianites and the Ishmaelites, with their camels and spices, on occasion, therefore, in addition trafficked in slave labour. All this agrees with what Bereshith has to tell us.

Yoseph Index Yoseph Sitemap Scripture History Through the Ages Yoseph Egyptian Adventure Yoseph Scriptures and Dreams The Plot Against Yoseph Yoseph's Brothers Cruel Seqel Yoseph In The House Of Potiphar Yoseph In Prison Pharaoh's Strange Dreams Yoseph Slave Becomes Viceroy Of Egypt Yoseph's Unexpected Family Reunion The Ten Brothers Before Yoseph Yacob Goes To Egypt Yoseph and the Death Of Yacob YAHWEH's Sword History Further Anxieties Of Yoseph's Brothers Yisraelites Remain In Egypt Period Of The Great Persecution