YISRAEL COMES OUT OF EGYPT

What was the size of the Yisraelites' camp as they left Egypt?

Hebrew emigrants that came with Yoseph and Yacob (ABOUT 1220 B.C.)

Bereshith (Genesis) gives full details of the number of Hebrew emigrants who came into the Delta in company with Yoseph and later with Yacob. There were seventy, not, of course, including women and young children, servants and slaves (Bereshith 46:26-27). Seventy, in fact, is a reasonable number for a medium-sized clan.

After four centuries in Goshen, the Hebrews left Egypt. According to Exodus there were six hundred thousand men, as well as their families. On this basis, it has been estimated that the total population of Hebrews in the Delta must have been two million. This is unlikely. In the first century B.C. all Egypt numbered only seven hundred thousand. It should be noticed, too, that the column of emigrants is said to have crossed the arm of the sea (called the Sea of Reeds in the Scriptures) in a single night; an impossibility for two million people. Such a multitude would, in any case, have covered twice the distance between the Delta and Sinai! Clearly the numbers given by those reporting them, and perhaps even by the scribes, have been increased so as to fit in with the epic style of the narrative. A cautious estimate might say that it was two to three thousand nomads who set out, and this in itself was a considerable number.

The Hebrews were joined by people of various sorts. .. in great numbers (Shemoth 12:8). Bemidbar mentions a ‘rabble’. These may have been slaves and prisoners of war who had been forced to make bricks, with probably some Asiatics left behind after the Hyksos invasion, Edomites, Midianites, etc. These disparate elements, always on the point of rebellion and criticism, were to prove a heavy burden to Mosheh whenever some difficulty or trial occurred.

On their journey they carried the unleavened flour under their cloaks in meal tubs: and a more weighty burden -Yoseph’s bones in a coffin shaped in Egyptian fashion. Their great ancestor’s wishes had to be respected. Before he died he had told them, solemnly: ‘It is sure that YAHWEH will visit you and when that day comes you must take my bones from here with you’ (Shemoth 13:19). Yoseph’s bones were to wander with the Hebrews during their ‘forty years’ journey in the region of Sinai. As soon as they reached Canaan they were anxious to bury them, and the burial took place at Shechem.

Camp was struck: the caravan set out.

The Yisraelites seek a way out

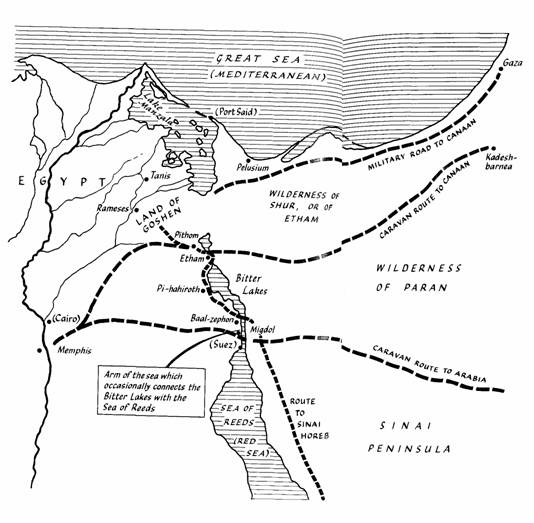

What route was followed by the Yisraelites? Egyptologists have studied this problem closely. Recent studies seem to have shown that in fact there was not one Exodus but three: 1. the northern route, towards Palestine (marked on the map as the route of the armies): 2. the central route, starting from Etham towards Palestine (marked on the map as the caravan route): 3. the southern route, west of the Bitter Lakes, and leading to Sinai: this was the caravan route of the Arab merchants. A short examination of these theories is here followed by a suggested solution of the problem.

THE YISRAELITES’ PROBABLE ROUTE

Leaving Oantir (to the south of Pi-Rameses) the column of Hebrews set out under Mosheh’ leadership.

It did not take the northern route, that is, the route taken by the armies into Canaan dominated by Sileh (elKantara). The column turned towards Etham (probably to take the caravan route). At Etham it wheeled round, but we do not know for what reason.

By way of Pi-harihoth it went down the western shore of the Bitter Lakes. The column crossed the series of marshes (dried up by the east wind) at the southern end of the Bitter Lakes, forming a sort of corridor intermittently covered by the Red Sea.

The first route

1. The first route, called that of ‘the armies’. It follows the Mediterranean coast-line up to Gaza.

There is general agreement nowadays that the migration started at Oantir, south of Tanis. In principle, the northern route, from Sileh, or the modern el- Kantara, below Lake Manzala, it seems, would be the one naturally indicated. In practice, it would have been disastrous. Recent excavations have shown that this region bristled with Egyptian fortresses erected to protect the Delta against the Asiatic invaders. The Hebrews, coming out of the Nile valley would have come up against this closely linked barrier. The Scriptures adds that it was also the direct way to Philistine territory, though in fact, the Philistines were not yet in occupation, and Semitic tribes held strongly fortified positions there. The Scripture is careful to tell us that the Hebrews did not travel along the route leading to the Philistines, and it offers a theological explanation: YAHWEH said that as the result of the inevitable battles, the people would change their minds and turn back to Egypt.

The second route

2. The second route; from Etham in the far north of the Bitter Lakes. It was a commercial highway, the caravan route, to Canaan by way of Kadesh, the opulent oasis in the desert of Paran. This raises a fresh problem.

The meeting place for the general departure is undisputed: it was Oantir, north of the Wadi Tumilat for them all. The Scripture indicates that the Hebrews began their journey from the south-east; they crossed the slopes of Goshen and by way of Succoth (the Tents), marched on Etham, the start of the caravan route to Kadesh. The road to freedom was open; they had only to cross the ford through that narrow marshy stretch (now widened by the Suez Canal) that had once connected the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. The Scripture suggests that the Hebrews advanced north-east of Etham so as to take the caravan route through Kadesh and Beersheba, straight into Canaan.

But at this point matters become complicated. What really happened? We know at least the previous order was countermanded: ‘Tell the sons of Yisrael to turn back and pitch camp in front of Pi-hahirath, between Migdal and the sea, facing Baal-zephan’ (Shemoth 14:1). Obviously something unforeseen had occurred, it may have been a foiled attack against an Egyptian outpost. Etham means a high wall and also a rampart.

At any rate there was a complete reversal of direction. They had been going east and then north-east. But now they turned south along the route following the shore of the Bitter Lakes. This was still in Egyptian territory.

It is possible -and a number of scholars hold this view -that some tribes, detached from the main body, may have been able to penetrate the line of defense unobserved, and move on towards Kadesh, where we find them a little later.

This being so, can we call this an Exodus in the strict sense? For these must have formed only a small contingent. The main body, led by Mosheh now moved south along the third route, the traditional direction of the Exodus.

The third route

The third route: from Etham to Migdol.

It was YAHWEH WHO, through Mosheh, his envoy, was leading the Yisraelites. At every turn the Scripture emphasizes this intervention of Providence. During the day, he went before them in the form of cloud, and during the night as a pillar of fire, to show them the way. It reminds one forcibly of the sandstorms that now and then swept through the desert like some mysterious force that seemed almost alive. The Arab drivers mutter: ‘It is a djinn who is passing by.’

Fr F. M. Abel, D.P., one of the most eminent scholars of the Scriptural School in Jerusalem, a historian and an archaeologist, examined, on the spot, the various hypotheses as to the route taken by Mosheh, and in the light of the information given by Scripture and of the geographical possibilities, worked out his own solution which is here followed.

Starting from Oantir in mid-Goshen, in two successive bodies, they stopped first at Etham. There followed a strange and sudden change of course towards the south, and they camped in front of Pi-hahiroth between Migdol and the sea, facing Baal-zephon (Shemoth 14:1-3). Speaking through Mosheh, YAHWEH told them: ‘You are to pitch your camp opposite this place, beside the sea.’

It is difficult to identify the places mentioned in the Scriptures, especially as some of the names it gives are simply descriptive. Migdol, for instance, is an Egyptian word for fortifications; Pi-hahiroth means the house on the marshes, or beside the marshes; Baal-zephon recalls a Canaanite god, the baal of the north, who may have been worshipped in very different places. All of this makes the historian’s task very difficult. There is no room here to discuss all the theories put forward. Here Fr Abel’s position -summarized by Fr Grollenberg of the same School, in his Atlas of the Bible -is accepted; in this view Migdol (a fortress) may well have been in the far south of the Bitter lakes in order to protect the fords; Etham (a rampart) was built for the same reason in the far north of this group of lakes; and Baal-zephon was slightly south-west of Migdol. There were others in the north.

Scripture speaks of the camp being set up by the seaside. Unfortunately Hebrew has a very limited vocabulary and has only one word to express both sea and lake.

At this remote period the Hebrews around Migdol lived, in fact, close to an arm of the Red Sea (or Sea of Reeds). The gulf of Suez, which then went further inland than today, reached as far as the Bitter lakes and ended there, though it was only intermittently, at some seasons or as the result of certain tides, that it penetrated so far. This natural waterway ran for nearly forty miles, and is now included in the Suez Canal. Its course was ill-defined, marshy and intersected by fords. At times it was dry, at others it became a bay, and occasionally it was just an arm of the sea that could not be crossed. It was only late in the “Christian” era that a ‘bar’ was formed, more or less isolating the Red Sea from the sheet of water called the Bitter lakes. But as late as 1860, Linant Bey recorded that during an equinoctial tide the Red Sea had pushed forward about ten miles towards the lakes. Today the Red Sea and the Bitter lakes are joined by the Suez Canal.

The Hebrews thus arrived at this ‘sea’, as it is called by the Scripture, but which was really an arm of the sea, a channel of salt water, a few hundred yards wide at most. How to cross it was a problem. Mosheh seems to have known the way perfectly; he had taken it as an exile to Midian, and on his return. The Hebrews prepared to cross by the traditional ford leading, on the Asiatic side, to the caravan route to Arabia by way of Sinai.

Back Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Index Next

Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Founders of the Nation Scripture History Through the Ages