THE TEN PLAGUES OF EGYPT

Passover; The Conclusion Of The Ten Plagues Plagues

History and the ten plagues; a parenthesis; explanation, emphasized and judgment

There are a number of important points to notice about the ancient account of the plagues.

To begin with, there are contradictions in the narrative that demand an explanation. Then its epic character must be emphasized; and finally, a detailed judgment on its value as history must be attempted.

There are many contradictory statements, and these are numerous enough to be disturbing, at least at first sight. For instance, in the account of the first plague, Mosheh is said to have taken his staff, struck the Nile and turned its water into blood (Shemoth 7:17). In verse 19 it is Aaron who is said to have done this. A little further on, we are told that it was the water of the river that became red, but a few lines after this, in the same chapter, we learn that this phenomenon also extended to the marshes, canals and even to the contents of every tub or jar. Again, in the account of his declaration about the coming darkness (ninth plague), Mosheh tells Pharaoh that he will not visit him again. But this does not prevent him, in the following chapter, from arriving to tell the king that the tenth, the last and most deadly plague was on the way. There are many repetitions in the story, and these unfortunate contradictions. Is this due to editorial carelessness, loose thinking or lack of skill? In no way In the sixth century B.C. when the scribe responsible for this book wrote the chapter we are considering, he made use of various historical sources that were at his disposal. These ‘traditions’ or ‘cycles’ have been previously discussed several times. Here it is sufficient to repeat briefly that in order to write the account of the plagues, the author made use of three main documentary sources: the Yahwistic -probably committed to writing in the tenth century, during Solomon’s reign; the Elohistic, slightly more recent than the former; and the Kohen, written after the return from Babylon about the middle of the seventh century B.C. 3

Instead of combining the various materials into a single new and personal narrative, as a modern historian would do, the sixth-century scribe took over whole phrases and even lengthy paragraphs from the manuscripts he was studying, and sometimes copied them word for word. All this was done without the least regard for repetitive statements or bothering about the contradictions that might appear here and there in his compilation.

Modern Hebrew scholars have succeeded in identifying; isolating and labeling all the individual items that together make up this account. They have ‘sounded’, so to say, each phrase of the Hebrew text, analyzing the syntax, setting apart the metaphors and the modes of expression personal to the author of each of these ‘cycles’, and so have been able to distinguish the origin of the main documentary sources used by the scribe in the construction of his work.

It will be obvious that these unedited texts are of inestimable value since they enable direct contact to be made with Yisraelite traditions of remote antiquity. The cost of this treasure may include some contradictions and some vagueness in detail. Does that matter? In any case, we should not be surprised to find that the three traditions record the ‘ten’ plagues differently: the Yahwistic author speaks of only seven ‘blows’, the Elohistic and the Kohen Code of only four. It is quite natural that as the centuries passed, the various human groups who preserved these ‘cycles’ should have attributed great importance to one episode, while neglecting another. It is, however, significant that all three cycles mention the tenth plague, the one in which the eldest son of every Egyptian family perished, and which finally decided Meneptah to let the Hebrews go. It was inevitable that the final editor should have included all ten plagues.

The modern reader may be shocked by this ‘feast of signs’ which began on Sinai (with Mosheh’ staff turned into a serpent), was continued in Pharaoh’s court (with Aaron’s staff turned into a serpent too), and ended in an apocalyptic climax with the successive plagues that struck Egypt and its people,

At this point we should remember that we are still in the archaic period of Yisrael’s story. But specialists in comparative literature have shown that in the remote and arduous origins of a great civilization, its primitive history takes an epic form: indeed, it is bound to take that form. Typical examples are: the Iliad, at the dawn of the Greek nation; the Song of Roland in France; the Scandinavian sagas, etc. They are always formed in the same way: on a theme whose authenticity is proclaimed with the utmost care (the Trojan war; the defeat of Charlemagne’s rearguard in the pass of Roncevaux; ihe expedition of the Norwegian drakkars in Greenland and America), and the popular imagination delights in decorating the life of the national hero with an infinity of wonderful traits. The modern historian has to re-establish the facts.

Does this mean that, in order to conform to the methods of these scholars, we must reduce the account of Mosheh’ adventures in Egypt and his endless conversations with Pharaoh, to a profane and purely naturalistic status? We certainly must not exaggerate either way, not even slightly; and on this subject there is no reason why we should accept everything or deny everything. For that would make the alternative to be either the somewhat naive ingenuity of past ages or mere desiccated skepticism. We dare not forget that the Scriptures are a living theological work whose aim is to recall the superb and formative dialogue between YAHWEH and man. It is an essentially spiritual realm, from which it would be extremely difficult to eliminate the supernatural on a priori grounds,

3 Yahwistic: this cycle is so called because in it the author calls ABBA YAHWEH The Elohistic calls HIM Elohim The Kohen’s code was produced by the kohen ) of the Temple in Jerusalem

Practical conclusion; YAHWEH acted in a new way

At this point in Yisrael’s history YAHWEH acted in a new way. This form of YAHWEH's intervention was absolutely necessary in this desperate situation, if the People of YAHWEH were to be saved.

Next, we notice that the Hebrew imagination reacting to these wonders -hard for an historian to define exactly furnished a generous response. Century after century it gave thanks for them, for was it not through them that YAHWEH had saved his people? The memory of them lay at the roots of Yisrael’s faith and hope.

Finally we must certainly admit a progressive expansion in the account of these events. Moreover, their use in worship as well as their epic style needs to be taken into account. It is all this that ultimately gave us the complex document represented by this book.

Before YAHWEH’s power in a final and frightful way, the tenth plague: the Passover in Egypt

Immediately preceding the further manifestation of YAHWEH’s power in a final and frightful way, the members of the Hebrew community in Egypt ate the Passover.

YAHWEH had thought fit to let Mosheh and Aaron know the exact date when the tenth plague would be unleashed. The two prophets were told that this time Pharaoh would be compelled to give Yisrael its freedom. When that happened the journey must be begun without delay, together with the women and children, the cattle and the baggage. Preparations for departure must be considered, and a detailed timetable was provided.

Before striking camp there was to be a meal of a liturgical nature, eaten at night. Its every detail was determined by Mosheh, and every family had to obey his instructions implicitly. As early as the tenth abib 4 each group of Hebrews were to select a kid or a Iamb, a male (Vayiqra (Leviticus) 1:3-22:19), an animal without blemish (Vayiqra 21:19, 21) and born during the year. Four days later, at the end of the afternoon of the fourteenth abib, and before sunset, this victim was to be slaughtered. With a branch of hyssop (a plant like marjoram, used as a sprinkier), previously steeped in the blood of the animal just slaughtered, the two doorposts supporting the entrance to the tent or the lintel of the dwelling were to be marked. The purpose of this was to warn the ‘Malak of YAHWEH’ to pass over and not to slay the firstborn in that place. But the Malak would enter the houses of the Egyptians, for these obviously would not have this sign outside, and slay their firstborn. Through this warning-note the Hebrew children would be spared.

Orientalists see in this red mark on the dwellings the defensive characteristic of blood which all Semites (even today the rite is strictly observed by some nomads of the Middle East) considered to be a means of keeping evil genii (or spirits) away. Ethnologists have discovered this custom in Africa and even in America.

The kid or Iamb was to be roasted whole, with its head, feet and entrails. It was strictly forbidden for it to be boiled in water. All of it had to be eaten during the meal; this was to prevent anything left over being profaned by the polytheistic Egyptians after the Hebrews had gone. If there were not sufficient members in a family to dispose of the animal entirely, neighbours (fellow-believers, of course) were to be called in. Any scraps that might still remain were to be burnt on the hearth. The greatest care had to be taken not to burn any bone of the victim. This reveals an ancient pastoral and Semitic custom; in the spring the firstborn of the flock was sacrificed to the genie spirit protecting the stock, and through this blood offering he was asked to secure the welfare of the animals. It was essential, therefore, not to provoke, by some magic, among the animals to be born later, those accidents which the shepherds dreaded: fractured feet.

Scriptural commentators have pointed out a very moving harmony. When MESSIYAH, YAHWEH’S Paschal LAMB, came to die on the cross, not a limb, not a bone was broken. This was directly contrary to the traditional method of punishment. For, normally, the condemned man, nailed to the stake by his hands and feet, died, not as is generally believed, from a heavy loss of blood, but from asphyxia. His arms were stretched out and his lungs were blocked. From time to time, in order to breathe, he lifted his body, at the cost of fearful pain, by supporting himself on his nailed feet. After being exposed for three hours, a Roman soldier, in charge of the execution, using his spear as a club, would break his legs in order to shorten the agony. Death from suffocation soon followed. In Scriptures, however, we read that a guard, in accordance with the regulations, broke the legs of the two thieves being crucified on either side of YAHSHUA, but when he reached YAHSHUA he found HIM dead, and so did not strike HIM, but simply pierced his heart with his spear, and water poured out. Thus on Calvary, the ‘Lamb of YAHWEH’ had no bone broken, just as the Law of Mosheh decreed for the sacrifice of the Iamb on the fourteenth abib, a rule based doubtless on an age-old custom of the Semitic shepherds.

Returning to the meal in the night, we find that the Iamb of the Hebrews had to be eaten with bitter herbs whose sharp taste was to recall in later times the bitter bondage in Egypt. Scripture does not tell us what plants these were; they are described in rabbinic tradition, though they must have varied at different times and places. It is generally agreed that they were mainly chicory, endive and cress, and probably parsley as well.

The bread to be eaten with the roasted meat was to be made without leaven (yeast). Although the date for departure had been already settled (the sacrificial Iamb was selected four days before it), this unleavened bread was meant to suggest sudden and extreme haste, the haste of a housewife with no time to let the bread rise. The people who ate would have to be content with flour mixed with a little water, and quickly baked.

The rite had an additional purpose. Symbolically, yeast contained the principle of its own corruption, and the Yisraelites were forbidden to offer fermented bread on YAHWEH’s altar, except in the case of peace offerings and during the feast ‘of Weeks’, that is, Pentecost.

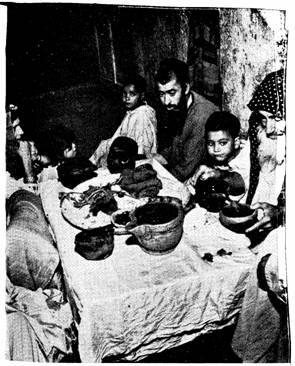

There was one other peculiarity about this meal. It was the custom in the East for a man to eat, squatting like a tailor, before a coloured skin placed on the floor, around which the family gathered. The dish was put in the middle and all took the food from it with their hands. But on this Passover night a very different attitude was adopted. Everyone stood, their long tunic gathered round their loins and fastened with a belt. With their sandals on their feet, and staffs in hand they were travellers, ready to start the moment the signal was given.

The tents and houses were shut. No Hebrew was to wander about outside. Every family was to assemble for the sacred meal. ‘You shall eat it hastily,’ YAHWEH told Mosheh, ‘it is a Passover in honour of YAHWEH.’

Observe the mouth of Abib and celebrate the Passover for YAHWEH your ABBA, because it was in the mouth of Abib that YAHWEH your ABBA brought you out of Egypt by night. ..For seven days you must eat [the victim] with unleavened bread, the bread of emergency, for it was in great haste that you came out of the land of Egypt; so you will remember, all the days of your life, the day you came out of the land of Egypt.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 16:1

4 The month of abib (the corn-month) was the sixth of the year Later, on account of the institution of the Passover, it became the first of the twelve months. Yisrael’s calendar was lunar, so it began with the new moon of the spring equinox.

Night of fear; The Tenth and last Plague (Shemoth 1-12:29-33).

While the Hebrews were eating this meal in silence and trembling, YAHWEH had unleashed the tenth liberating plague over Egypt, the one recorded by all three traditions. During this night of fear, says the Hebrew author of this epic, the firstborn of every Egyptian family died without apparent cause. There was a great cry, for there was not a house without its dead. Pharaoh’s son, the future successor to the throne, was not spared, any more than the prisoner in his dungeon. This time the trial was overwhelming. Pharaoh did not wait for dawn before summoning Mosheh to the palace; he said to HIM: ‘Get up you and the sons of Yisrael, and get away from my people. Go and offer worship to YAHWEH as you have asked. ... Take your flocks and herds and go.’

Throughout the Delta in mourning a great cry arose. Women in the East, when a near relation dies, howl as a sign of their grief. It is understandable that in the situation in Egypt the people would have clamoured for the immediate departure of the Hebrews. Everything was ready for the road. When he left the palace, Mosheh, therefore, had only one command to give, and straightaway, even before dawn, the people were on the move. The captivity in Egypt was over. The exodus had begun, and the climax of the epic had been reached.

Back Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Index Next

Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Founders of the Nation Scripture History Through the Ages