In Parenthesis: David And The Tehillim

The narrative must here be briefly interrupted in order to observe David in a new light, that of 'the psalmist'.

There is a dramatic fitness in discussing the matter at this point. Saul's agents were about to enter the house. David's life seemed to be nearing its end. He took his harp and addressed a fervent prayer to YAHWEH, begging him, in his mercy, to save him from this imminent danger. This was expressed in the lyrical notes of Tehillim 59. 7 accompanied on the harp in the traditional way. Some scholars ascribe this great poem to the events related here. The appeal to the Almighty begins with this heart-rending cry:

Rescue me from my enemies, my YAHWEH

protect me from

those attacking me,

rescue me from these evil men,

save me from these murderer's.

As the events of David's life unfold, the poems that David may have composed in relation to them will be referred to in this context. But the question at once arises: should David be considered to be the author of the Tehillims? And if not, can any of them be attributed to him with some degree of certainty? At this point we must insert a brief but necessary parenthesis, for in these volumes the historical criticism of the Tehillims as a whole will not be discussed again.

The word 'psalm' is directly derived from the Greek psalterion, a stringed instrument used for accompanying the singing of a poem. The musical directions at the beginning of each Tehillim mean little to us. They frequently indicate a tune, known to the people, (to the tune: 'Of the lilies'; to that of 'The Doe of the Dawn'; 'For sickness', etc) according to which a given psalm should be sung.

The psalter in the Bible contains 150 psalms. Formerly, an excessive traditionalism insisted that it was entirely David's creation. At the end of the last century, the ultra-critical school fell into the opposite extreme; these historians held that not a single psalm had David as its author. Today, a wide range of Scriptural scholars adopt a less rigid attitude, and divide the psalms into three main categories:--

1. Those earlier than David, of which some fragments have come down to us.

2. Those later than David, the work of various inspired scribes during the period of the kings, or in the centuries after the return from the Babylonian Exile (538 B.C.).

3. Those composed at the time of David, whose authors were:

(a) Professional cantors (the sons of Korah; the sons of Asaph, etc); their work was to write the liturgical music to be performed before the Ark in the Tabernacle of YAHWEH in Yerusalem.

(b) David himself, In the course of this work will be mentioned in chronological order, those psalms which, partly or in their entirety, may be attributed to him.

About half of the Psalter may be by David -unless some of the psalms ascribed to him, are in fact simply 'dedicated' to him. Sound criticism is forced to admit that a number of them bear the marks of his genius. But each example must be discussed on its own merits. The difficulties encountered by literary criticism and philological investigation are due to the fact that in the course of centuries, the various psalms attributed to David underwent revision and correction, and received fresh additions. They were in constant use in worship in the Tabernacle and, later, in synagogues, In the course of the centuries of use they would very probably have been modified and expanded.

7 Of David. When Saul sent spies to his house to have him killed. These title and inscriptions of the Tehillims must be taken simply as indications. inserted later. They are often questionable.

David Escapes From The Fortress Of Gibeah

Michal said to her husband: 'If you do not escape tonight you will be a dead man tomorrow.' Taking advantage of the dusk, he escaped through a window.

It was just in time. Saul's agents soon arrived to lay hold of his son-in-law. To gain time, and to enable her husband to get ahead of his pursuers, Michal arranged a clever deception. She put a teraphim in her husband's bed, covered it with a garment and put a truss of goat's hair on its head. When her father's men arrived, she pointed to the dummy, and said: 'He is ill,' and dismissed them without more ado. Discomforted, they made their report to Saul who at once fell into a great rage. He told them to go back to David's home and seize him. 'Bring him to me on his bed,' he shouted, 'for me to kill him.' But it was far too late. David had already escaped.

He stopped en route at Ramah, where he paid a visit to Schmuel. The old prophet seemed uncertain what he could do about the king of Yisrael of whose conduct, however, he still disapproved. But he prayed that YAHWEH would protect the young man from Bethlehem whom he had anointed with the qadash oil.

Jonathan, David's great friend, did his utmost to effect a reconciliation. He began by cautiously sounding his father but Saul replied with insults and with threats of death for David. He cursed his son, and in a dramatic interview, tried to kill him. There was not the least hope of settling matters, the king's mind was driven towards crime. With great difficulty, Jonathan managed to meet David in the fields. He gave him an impartial account of the position. They shed many tears together, and when they parted, Jonathan spoke the traditional words: 'Go in peace.' They said good-bye with heavy hearts, and David took the road to the south, the road to exile.

8 Teraphim This obviously had nothing in common with the little idols which Rachel stole from her father and hid in the pack-saddle of her camel (cf Isaac and Yacob, p 66) Michal's teraphim however must have been life-size. It is surprising that an idol of this kind should have had a place in authentic Yahwist circles, for this cult belonged to early Semitic beliefs. Was the teraphim described here Michal's personal property? Did David merely tolerate it in his house? Or did he also have recourse to this instrument of divination? It must be added at once that the way in which it was questioned or the methods used in interpreting its supposed replies, are not known. For the historian, it all remains shrouded in obscurity. The scribe's prejudiced account should be noted; he was opposed to this practice with its magical aspect, and stressed the somewhat comic function of the idol used for this trick.

David Joins The Resistance

After his great period as a victor, David now entered his time of trial. The former leader of Yisrael's armies had become an outlaw. And time, far from easing the position, made it worse. It was not a promising development, and it had four results.

First of all, David appears as a mere fugitive, compelled by prudence to run away. But Saul soon set out in furious pursuit of his former subordinate; and then matters developed into serious guerilla warfare.

This, however, in no way prevented David from carrying out a shrewd policy of matrimonial alliances in the south; he seems cleverly to have prepared for the future.

But ultimately the conflict between Saul's army and that of the former shepherd of Bethlehem and his group of outlaws, proved radically unequal. So David gave it up, and went over to the hereditary enemy, the Philistines. Did this mean that his adventure was over?

David, The Outlaw In Flight

Ancient traditions record several vivid and colorful incidents in the fugitive's wandering life.

His first stop was at Nob, a short distance from Gibeah, identified today as Mount Scopus, east of Yerusalem. Ahimelech, the kohen of the place, was a descendant of Eli; the Shiloh kohens had fled to Nob after the city, in which the Ark was kept, had been destroyed. Ahimelech expressed some surprise at seeing the king's son-in-law without arms or escort. David, never at a loss for an explanation, said that he had been obliged to leave Gibeah in haste and had agreed to meet his men a little further on. In the hurry of his departure, he had had no time to take a sword, and asked Ahimelech to give him Goliath's; this memorable trophy had been reverently placed behind the ephod 9 of the tabernacle.

He also asked Ahimelech to give him food, but the kohen had only consecrated loaves to offer him -little rolls put 'before YAHWEH' in the tabernacle, and, in principle, reserved to the kohens. Ahimelech hesitated for a moment, but then considered that a relative of the king could not be allowed to starve. He asked David whether he was in a state of ritual purity (that is abstaining from sexual intercourse). David answered that soldiers on active service always were. And then, with Goliath's sword and the set apart loaves, he resumed his journey.

He decided to make his way to the territory of the Philistines. There he would be safe from Saul's enquiries. He approached Gath, Goliath's native city. But as soon as he arrived he was recognized and pursued. As a measure of security he played the madman. The gates were then opened to him, for in ancient times, insanity was thought to give its victim a set apart and inviolable character. 10

After reflection, in the circumstances he decided that his most prudent course was to return to Yahudah. So he took refuge in the Cave of Adullam, a kind of natural citadel, west of Bethlehem. It is a hilly and comparatively well-watered neighbourhood. He was now no longer alone; he had been joined by relatives and friends against whom the law of the blood-feud automatically came into force.

He immediately became the leader of the resistance, a respected head of four hundred outlaws -homeless men, rebels, malcontents and adventurers. They managed to exist by means of raids, marauding, robbery and violence.

He was anxious to preserve freedom of movement and therefore decided to keep his family away from the conflicts in which he was inevitably involved. He took them to Moab, on the east of the Dead Sea, then he came back to the hills of Yahudah and awaited events. The king's forces were unquestionably superior, but he had by no means lost hope. He realized that at any moment he might have to meet Saul's men, but even with his mere handful of supporters he was ready to oppose them.

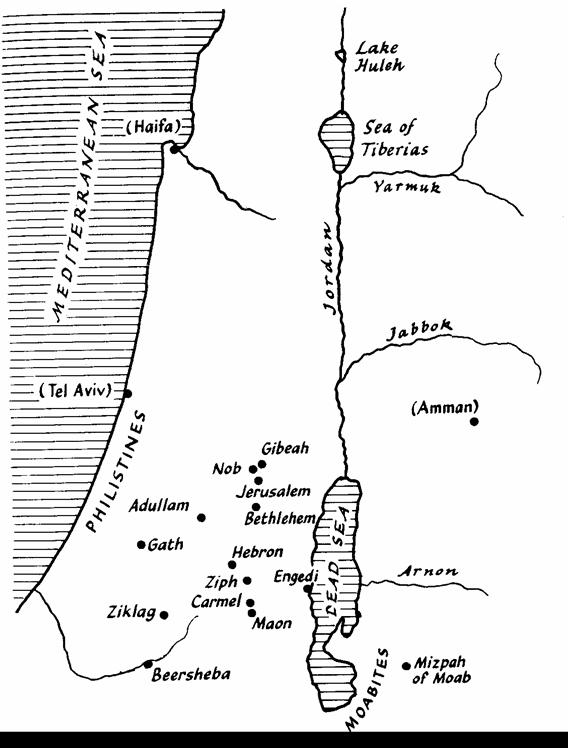

DAVID'S FLIGHT FROM SAUL

To escape a worse plight David was obliged to flee from the royal court at Gibeah where Saul reigned. He went by way of Nob, and sought refuge at Gath in Philistia. Then he returned to Yahudah. He thought it advisable to take his family to Moab (south-east of the Dead Sea) where he placed his family in safety.

Adventures in the cave of Engedi; then in the desert of Ziph. In the end to escape Saul's vengeance David was obliged to leave his own country Once more he went to Philistia and gave his services to Achis

9 Another instrument used in divination. It will be discussed again shortly David used it throughout his period of exile as a means of questioning YAHWEH. It is clear that Canaanite ritual magic had penetrated deeply into Yahwist circles

10 Tehillim 56 may have been composed at this time. Some believe that it contains ancient elements and that David may well have been its author. It begins with an appeal to the Almighty: Take pity on me, YAHWEH, as they harry me...All day my opponents harry me. It ends in thanksgiving: for you have rescued me from Death to walk in the presence of YAHWEH in the light of the living. As regards Tehillim 34, the inscription at the beginning asserting it to have been composed by David in thanksgiving to YAHWEH for enabling him to leave Gath, is open to serious question. At least in its present acrostic form -each verse beginning with a different letter, in the order of the Hebrew alphabet -it is certainly of a date later than the Babylonian Exile, the return from which occurred in 538 B.C.

King David and the Foundation of Yerusalem Index King David Sitemap Scripture History Through the Ages