Samson The Giant And Popular Hero

(Shophtim 13). About 1075 B.C.

4th Judge

There were three judges after Jephthah; to each of them the Bible devotes only some three to five lines. They were Ibzan, Elon and Abdon, leading men who by their example helped to keep Yahwism alive.

We now come to a very strongly marked personality, Samson, the popular hero of independence, the brave giant endowed with extraordinary strength. With obvious satisfaction the writer recounts for us the adventures of this strong man in a sequence of anecdotes full of fanciful incident. The morality of some of the stories is a little doubtful on occasion and the historian feels bound to regard certain features, which are obvious additions, with considerable reservations. Nevertheless, the chapter devoted to Samson is certainly the most picturesque in the Book of Shophtim and this explains its popularity.

Samson in fact conducted a personal war against the Philistines, the hated enemies who had only settled recently in the land of Canaan and constituted an obvious danger for the political future of the Yisraelites. Samson continually set traps for them; sometimes he played outrageous tricks on them, at other times he killed great numbers of them. Since the Yisraelites could not be victorious on the field of battle they consoled themselves by covering the Philistines with ridicule. In this way, popular stories about Samson, which were passed from mouth to mouth and told repeatedly among the small clans in the south constituted a continual call to resistance.

The theme of these racy pages was the struggle of a national hero against the Philistines, a new people who had arrived in the Near East. They have not so far been mentioned here.7 Since these people played a considerable role in the history of Yisrael something must now be said about them.

The Philistines Were Indo-Europeans. A little more than a century before the events here concerning us an Aryan group, migrating slowly from the remote tablelands of upper Asia, penetrated with its chariots into Europe by way of the Balkans. These peoples had settled in the islands of the Aegean Sea and in the coastal provinces of the peninsula which at a later date was named Greece. During the upheaval caused by the invasion of this part of the world there took place the celebrated expedition against the Aegean citadel of Troy.

Towards the middle of the twelfth century occurred a second wave of Aryans, following very nearly the same route as the first. To obtain a favourable place in which to settle the new arrivals drove out those who had previously settled in the Aegean. In these circumstances there was thus a huge mass of Aryan people obliged to depart hastily from Greece and the islands and to seek fresh territory in which to settle. They turned towards the delta of the Nile whose agricultural wealth was proverbial.

At the end of the thirteenth century the Aryans (the Egyptians gave them the name of 'Peoples of the Sea') attacked the mouth of the Nile from the west, that is, through Libya. Rameses III (1197-1165) inflicted a severe defeat on them and threw them back. In 1190 they attacked again, this time from the east of the Delta. Once more Rameses repulsed them. The Philistines, as we call them, then turned towards objectives which were less well defended; they settled to the south of Canaan in the rich plains of Sharon and, especially, of Shephelah, hitherto occupied by various Semitic tribes. The new masters of the territory quickly set up a kind of political federation. There were five kingdoms: Gaza, Gath, Ashdod, Ashkelon, and Ekron. On the other hand, the Zekals, their brothers in arms, settled in the region of Carmel.

For Yisrael the situation was an anxious one. The Philistines, who suddenly appeared on the scene early in the twelfth century (about 1190) were far more dangerous opponents than the native Canaanites and far more formidable than the nomad brigands of TransYardenia, the Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites. The Philistines were imperialists and within a short space they intended to annex the whole of the region situated between the wilderness of Negeb (to the south) and lake Tiberias (to the north).8 Now the Yisraelites, too, intended to possess this region, which they considered as their own property. The conflict was not long in coming. The story of Samson shows us the first engagements in this relentless struggle.

The Yisraelite tribes were still at a primitive stage of political development, but it did not prevent their realizing to the full what was at stake. It was a question of life or death. By making their theme a village epic, part dramatic, part amusing -namely the story of Samson -the Yisraelite story-tellers endeavored to uphold the morale of their co-spiritualists. The national hero is intended at every turn of the story to remind the audience of the presence of the terrible Philistine danger.

From the point of view of the liberation of the Yisraelites Samson could not be placed on an equal footing with Gideon or Jephthah. His role, more literary than effective, consisted of maintaining among the followers of YAHWEH the spirit of revenge against the 'uncircumcised' Philistines, with whom it was important not to come to terms on any pretext whatever. So we have this series of incidents filled out with more or less humorous asides.

The stories about women were cleverly exploited, as was proper in a popular narrative. Samson was betrayed by the woman whom he wished to take as his wife from among the Philistines, so he slew thirty of the uncircumcised and, full of wrath, returned to his father's house. One day he had the idea of visiting the woman who had laughed at him: he found her married to another man. In revenge for this supposed affront Sampson captured three hundred foxes, and tying them tail to tail put a lighted torch between each pair of tails. He then let them loose in the Philistines' cornfields.

These were good stories; they provoked the admiration of the Yisraelites-and consoled them a little for the advantages continually being gained by their opponents. Then there was the jawbone of an ass which Samson picked up on the town rubbish heap. With this improvised club and alone against a great multitude Samson slew a thousand of them. As he felt very thirsty after this exploit YAHWEH caused a spring of water to burst forth. All this was calculated to breed enthusiasm. Soon afterwards we come to the episode at Gaza. In this city of the Philistine confederation Samson had visited a prostitute. Hearing of this the Philistines at once planned to seize their enemy; for this purpose the gates of the city were closed. The next morning Samson found the way barred when he tried to leave. Thereupon, he calmly unhinged the gates, tore up the posts, hoisted them on his back and made his way towards Hebron.

Lastly, there was the episode of Delilah -her name means 'informer' or 'spy'. The Philistine chiefs had promised her eleven hundred silver shekels as the price of her betrayal. Samson, treacherously implored by his lover to reveal to her the secret of his great strength, in the end gave her the desired explanation. From the time of his birth, he told her, he had been a 'nazir', that is, he was consecrated to YAHWEH by his mother. In accordance with the custom of the nazirs he kept all his hair: 'A razor has never touched my head...If my head were shorn, then my power would leave me and I should lose my strength and become like any other man.' So Delilah had discovered what she had been asked to find out.

While Samson was asleep Delilah summoned one of her accomplices who sheared the seven locks off his head. Philistines, who were waiting in the next room, then fell upon Samson, and he could offer them no resistance. He was chained up and his eyes were put out; they then put him to turn the mill in the prison.

The great joy of the Philistines may be imagined. A little later, during a ceremony in the temple of Dagon, the chiefs of the Philistines ordered Samson to be brought before them: 'Send Samson out to amuse us,' they said. The Philistines had no idea (the Yisraelite story-teller appears to have been determined to portray them as almost simple-minded) that since Samson's hair had grown again he would have recovered his former great strength. The rest of the story is well known. Samson asked the boy who was leading him to take him where he could touch the central pillars supporting the heavy roof of the building. With one great effort, exerted by pushing his arms outwards, he managed to bring down these two great masses of masonry. 'May I die with the Philistines! He cried. The whole building fell down on the chiefs and on the people filling the sanctuary of the god. It was a fine story whose popularity among the Yisraelites cannot be doubted. But they were still at too primitive a stage of development to appreciate the great moral lesson which emerged from the story of their hero. They did not understand clearly that Samson's prodigious strength was merely a physical gift given by YAHWEH. His hair, which he was obliged to wear long as a nazir, had nothing to do with his superhuman strength. His long hair was only the external sign of his consecrated state, just as nowadays, a monk's tonsure is. That Samson lost his strength is explained by the fact that, gradually, he was false to his nazirite vow. That later, in prison, he grew as strong as he had been previously was the result of contrition, prayer and penance. That is the moral lesson that the writer wished to emphasize: in a time of trial it is only return to YAHWEH that is effective.

Deborah's period as Judge amounts to an attempt at union of the Yisraelite tribes of the north and south against danger from within the country, that is, the Canaanite power.

With Gideon and Jephthah it was two short-lived sovereignties which attempted in vain to rally the tribes in the north against a foreign enemy, the Midianites, Moabites and Ammonites, the nomad brigands of TransYardenia.

With Samson we have a wholly different conception in the form of a fable: Yisrael must not forget that it must fight with all its strength and on all occasions against the Philistines, the new and formidable enemy from beyond the seas. In this way, therefore, Samson took his place, in his own rather special way, in the list of authentic Shophtim.

It was not very clear at the time where all these isolated, uncoordinated actions were to lead. Fortunately, the Yisraelites soon came to understand that their independence, and indeed their very existence, could only be assured by achieving unity under the command of a single leader. And so we witness the appearance of the prophet Schmuel, YAHWEH's energetic spokesman. Endowed with uncommon spiritual strength, and in somewhat picturesque circumstances, he was to perform the anointing of Saul and David, the first two kings of Yisrael.

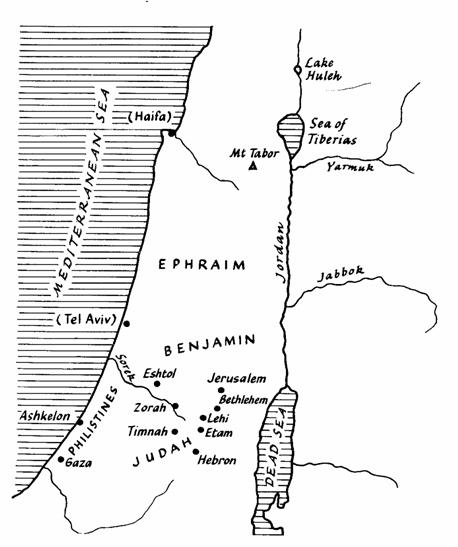

THE FIELD OF ACTION OF SAMSON. THE POPULAR HERO (about 1075)

The preceding campaigns of the Shophtim (those, at least so far examined in this book) took place either in the north (Deborah) or in the central part of the country (Gideon, Jephthah).

The picturesque adventures of Samson occurred in the south, in Yahudah and Philistia Samson: born at Zorah; 'Philistine marriage' at Timnah; journey to Ashkelon where he killed thirty Philistines.

Samson at the cave of Etam. The Philistines penetrate into Yahudah, settle at Lehi. Anecdote of the jawbone of an ass (Ramath-lehi). Anecdote of Gaza. Samson and the gates of the city.

Delilah of the Vale of Sorek. Capture of Samson, his death at Gaza.

'Listen, you kings! Give ear you princes!

From me, from me comes a song for YAHWEH.

I will glorify YAHWEH, Sovereign Ruler of Yisrael ...

'Then Yisrael marched down to the gates;

YAHWEH's people, like heroes,..

'So perish all your enemies, YAHWEH!

And let those who love you be like the sun

When HE arises in all HIS strength.'

Shophtim 5

7 The name Philistine was used by the writer of Shophtim in the chapter concerning Jephthah when enumerating the peoples who were Yisrael's enemies. But many Scriptural scholars consider that these lists were revised at a late dl and so they cannot be taken as an historical reference.

8 The name Palestine or Philistia means land of the Philistines These Philistines were a strange mixture of Indo-Europeans and Aegeans (the latter being, it should be noticed, neither Semites nor Indo-Europeans) who on their journey westwards had made a more or less long halt on Crete. It was the southern coast of Canaan, where the Philistines originally settled, which was first called Philistia. That was logical enough. But later on, by some strange confusion, the land of Canaan, which had become the land of Yisrael, was given the name of Palestine. Thus through the mistake of ill-informed geographers the Yisraelites owed to the Philistines, their implacable enemies. the official name of the Promised land.

King David and the Foundation of Yerusalem Index King David Sitemap Scripture History Through the Ages