YAHWEH's COVENANT ON SINAI

Set Apart Kohen, Organization of Camp and Passover

The new tablets of the Law; Mosheh’ radiant face (Shemoth 34:29-35)

When YAHWEH summoned Mosheh in the cloud on the upper slopes of Mount Sinai to communicate the text of the new Covenant HE gave the following instructions: ‘Cut two tablets of stone like the first and come up to ME on the mountain, and I will inscribe on them the words that were on the first tablets which you broke.’

So after this further period of forty days, when Mosheh went down to the Hebrew camp on the plain, he carried the text of the Law inscribed on stone to replace the one he had previously destroyed in a fit of anger at the sight of the golden calf. There was a further surprise, this time for the Yisraelites. For the skin on his face was radiant after speaking with YAHWEH. And when Aaron and all the sons of Yisrael saw Mosheh, the skin on his face shone so much that they would not venture near him. But Mosheh called to them, and Aaron with all the leaders of the community came back to him; and he spoke to them. Then all the sons of Yisrael came closer, and he passed on to them all the orders that YAHWEH had given him on the mountain of Sinai (Shemoth 34: 29-32). 10

Out of humility Mosheh henceforward placed a veil over his face. He removed it only in the Tabernacle when he ‘conversed’ with YAHWEH.

10 ‘The skin on his face was radiant’. The reader probably knows, at least through reproductions, the splendid marble statue of Mosheh by Michelangelo. The sculptor, to show on Mosheh’ face a reflection of YAHWEH’s splendor has given him, two rams horns This is explained by the fact that the sculptor followed the Vulgate whose author in this passage translated the original text in too literal a fashion. In Hebrew the verb qaran (give out rays) is associated with the substantive qeren (horn) -the horn of certain animals, the ox, for example, was compared poetically to a ray of light. The Latin author of the Vulgate has translated this passage by the words ‘His face was horned’. Nowadays orienta!ists correct the passage to ‘his face was shining’. Michelangelo’s Mosheh has served as a model for many sculptors and painters; hence these unexpected horns with which Mosheh is bedecked.

The building of the tabernacle, a Dwelling for YAHWEH

Accordingly without delay they had to proceed with the building of the tabernacle which served as a Dwelling for YAHWEH. Mosheh therefore summoned the most skilled workmen from among the different tribes. In fact some of the Yisraelites had previously belonged to the Egyptian workshops where they had acquired the necessary technical skills. At once these various specialists, goldsmiths, metal workers, carpenters, weavers, tanners and decorators came forward, enthusiastically offering their services. At their head Mosheh appointed a clever leader of the name of Bezalel with a certain Oholiab as his assistant.

In addition, the people were invited to provide on the basis of voluntary contributions the raw materials for the construction and adornment of the Dwelling. Here, too, the request was heard and answered with enthusiasm. From all sides there flowed gold, silver and bronze; purple stuffs, of violet shade and red, crimson stuffs, fine linen, goats’ hair, rams’ skins dyed red and fine leather, acacia wood, oil for the light spices for the chrism and for the fragrant incense; onyx stones and gems. (Shemoth 35:5-9). The offerings were so plentiful that soon Mosheh was obliged to have it proclaimed throughout the camp that the collection had come to an end as the craftsmen had now enough materials for their work.

When the tents of the Yisraelites had been in position for nine months at the foot of Sinai the work of building the sanctuary was finished.

The Setting Apart of the kohen and the tragedy of Aaron’s sons (Shemoth 40, Vayiqra 8)

Directions for this had been given to Mosheh by YAHWEH. Aaron and his sons came forward across the court towards the Tent of Meeting, but halted at the bronze basin to carry out the ritual washing -of their hands and feet -as a sign of purification. Then they went towards the Tent; on the threshold Mosheh awaited them (see plan of the Dwelling).

Mosheh then, with consecrated oil, anointed Aaron and his sons on their foreheads and on each he put a linen tunic. Thus was conferred on them the priesthood in perpetuity from generation to generation. Vayiqra provides a detailed description of the ordination rite. The central theme of the rite, as it is described, certainly goes back to the Mosaic period. But if the modern reader is brave enough to read these endless and detailed liturgical directions he must not forget that until the sixth century B.C. the ceremonial in question was revised, augmented and embellished by successive generations of oriental liturgists. It is not, therefore, an exact account of the investiture of Aaron that we have here but rather, historically speaking, the consecration of a Jewish high kohen after the return from the Babylonian exile (538 B.C.). And the same applies, of course, to the complicated ritual of the various and very numerous sacrifices.

On the same day that Aaron was anointed with oil a tragedy occurred: two of Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu were imprudent and irreverent enough to place in their censers unlawful fire before YAHWEH, fire which he had not prescribed for them (Vayiqra 10). It should be pointed out here that in the East ceremonial assumes considerable importance, the least gesture wrongly executed by the kohen inevitably placing the full effect of the sacrifice in peril. Everything that is laid down must be carried out to the last detail. Scriptural scholars regard this account as a moral fable in the form of a tragedy intended to warn officiants against liturgical mistakes of any kind.

Shortly afterwards, we find the ‘princes’, that is, the leaders of the twelve tribes, going to the sanctuary to present their offerings. The conclusion of the liturgical ceremonies for the inauguration of the sanctuary was marked by the consecration of the Levites (Bemidbar 8:5-6), which most Scriptural commentators regard as an anticipation of what was done some centuries later. A short explanation is required here. Aaron, like his brother Mosheh, belonged to the tribe of Levi. Henceforward, after Aaron’s consecration, both he and his descendants were kohen of Yisrael, set apart ministers. The other men of the tribe of Levi, now called Levites, did not share in the ke hunnah (priesthood) but they were the kohen assistants, serving the altars and, on journeys, carrying the various components of the Dwelling. Kohen and Levites must not therefore be confused, although they always worked in conjunction with each other. The Levites began their functions at the age of twenty and continued in them until they were fifty, though after this age they still helped, so far as they could and were able, the Levites in office. Here again, a distinction which only emerged later may have been attributed to the time of Mosheh.

The Yisraelites’ portable Tabernacle had now been completed. The ke hunnah (priesthood) had been instituted; the service of the tabernacle was organized. YAHWEH was now ready, according to the somewhat primitive ideas of the Mosaic period, to set out over the paths and tracks of the steppe where HE was to accompany HIS people as their protector.

Organization of the journey; establishment of the camp

Very soon, then, they had to set out again, taking with them YAHWEH’s Dwelling. Briefly, the following was the order in which they marched.

Mosheh showed himself in all circumstances, a first-rate organizer; he began now by taking a census of the tribes, since it was of prime importance to have an accurate idea of the military strength that could be put into the field, for it was very probable that on their journey they would be obliged to join battle. Already, of course, a first census had been held for the levying of the poll-tax (Shemoth 30:11-16); the second was carried out easily and rapidly. The statement in the Book of Bemidbar that there were 603,550 men at arms able if necessary to take part in a battle gives the impression that the total population of the tribes of Yisrael was between two and three millions; it has been pointed out on several occasions that the ancient East had a great tendency to exaggerate numbers.

The term ‘the twelve tribes’ has already been employed, but should be used with caution, for in fact it was only with Joshua and the ceremony at Shechem that it is really correct to speak of the twelve tribes. Before Shechem, there were probably not quite so many. The repeated use of the term the ‘twelve tribes’ and, more especially, of their names, and of the names of the chiefs incorporated in the census by Mosheh, appears to be of a much later period. They may well have been inserted in the text in order to guarantee the rights of the various Yisraelite groups at the time of the territorial division of the land of Canaan.

The census of the tribe of Levi, the priestly caste, exempt from military service, was carried out in a special way. The descendants of Levi were given a special status, differentiating them from the other Yisraelites.

The following was the order to be adopted so far as possible, according to the Book of Bemidbar, as the Yisraelites moved over the tracks of the wilderness.

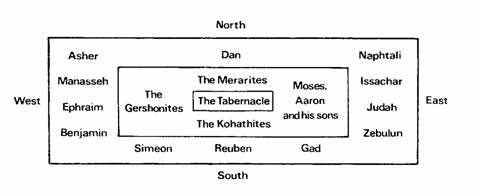

In the vanguard, one behind the other marched the tribes of Judah, Issachar and Zebulun. They were followed by a further body made up of the tribes of Reuben, Simeon and Gad. Next came the band of Levites carrying the various parts of the dismantled Tabernacle, followed by the Dwelling of YAHWEH, with its various components partially dismantled and carefully wrapped in skins and hangings so as to be hidden from the eyes of all. Then followed the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh. The rearguard was formed by the tribes of Benjamin, Asher and Naphtali.11 When they halted the tribes took up their positions around the tabernacle in the form of a threefold quadrilateral, as shown by the diagram below.

11 That is the order given by Bemidbar 2:1-34; it varies slightly from that given in Bemidbar 10:12-28

Before leaving Sinai: the second Passover (Bemidbar 9:1-14)

A year had already passed since the Yisraelites had fled from the Egyptian bondage.

The first Passover had been celebrated in an atmosphere of drama on the night when they had left the land of Egypt. The second Passover was celebrated at the foot of Sinai before leaving the SET APART mountain for ever; it took place in an atmosphere of gladness and hope.

On this occasion the Scripture repeats the prescriptions; a paragraph, obviously of a later date than the period concerning us here, gives instructions which proved very useful for the Jews of the diaspora, 12 who were absent from Judaea on the occasion of a journey or who were permanently settled in a foreign land; they were under strict obligation to keep the Passover with all the laws and customs proper to it.

12 The diaspora is the name of the Jewish colonies in pagan lands After AD. 70, the year of the destruction of Jerusalem by the Roman armies, the history of the diaspora became the history of the Jews.

The Yisraelites leave Sinai as the cloud lifted over the tabernacle (Bemidbar 10:11-28, 33-36)

It was in the second year, in the second month, on the twentieth day of the month, that the great departure took place. As the Yisraelites had arrived at Sinai in the third month of the first year (Shemoth 19:1), their stay in the region of Sinai lasted a little less than a year. They left Sinai a month after the end of the Passover celebrated there.

On that morning, in the plain at the foot of the mountains, the Yisraelites lined up in the order laid down: by ‘houses’, by clans, by tribes. Men, women and children surrounded the flocks; the tents and baggage had already been loaded on the donkeys.

The cloud 13 lifted over the tabernacle of Witness; this was the signal awaited by Mosheh. At once Aaron and one of his sons sounded the silver trumpets. On all sides rose up the ritual acclamations. The tribes of Judah, Issachar and Zebulun then set out towards the north and the wilderness of Paran. The Levites had quickly dismantled the Dwelling. Just as the Ark of the Covenant, taken up by the porters, was on the point of joining the column, Mosheh addressed this invocation to YAHWEH: Arise, YAHWEH, may your enemies be scattered and those who hate you run!

Behind the tabernacle the other tribes, drawn up in their strict order, moved forward. The Chosen People, carrying the Dwelling of their invisible ABBA, set out towards Kadesh, the great oasis of the wilderness of Paran, a very suitable base for an attack on Palestine.

13 This cloud has already been mentioned. It led the Yisraelites, the Scripture tells us, on the route from Egypt to Sinai, and once more from Sinai to Kadesh, then from Kadesh to the Promised Land. It marked out the route to be followed by the caravan, rising to indicate the time for departure, coming to rest to show a halt. The various traditional cycles used by the writer of the Pentateuch do not agree very closely in describing this cloud. To the Yahwistic tradition it is a column of cloud and a column of fire; for the Elohistic tradition it is a dark cloud; in the Kohen tradition during the night there appeared the ‘splendor of YAHWEH’, a sort of consuming fire, moving from place to place like YAHWEH HIMSELF. These different images, undeniably belonging to the epic style, agree in principle their object is to suggest the real presence of YAHWEH, accompanying HIS tabernacle, step by step.

Back Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Index Next

Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Founders of the Nation Scripture History Through the Ages