MOSHEH’ SOJOURN IN MIDIAN

The geographical position and characteristics of the people of Midian

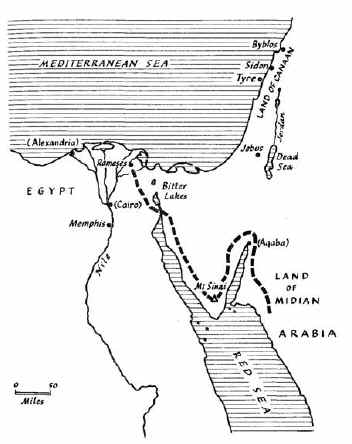

Mosheh fled from Pharaoh and made for the land of Midian (Shemoth (Exodus) 2:15).

The Scriptural scribe appears to have taken the relevant facts about the situation of this country for granted, and so does not pause to give us any information about it. Nor do the succeeding chapters describe its geographical position or the racial characteristics of its people. It is left to the student to find all this out.

The shepherd nomad Midianites and their Fertile Crescent country

What then was their origin? According to the Scriptures we should consider them as remote descendants of Abraham.

It says that Midian was the son of Keturah, one of the servants selected by Abraham as a concubine after Sarah’s death. In order to avoid disputes with Yitschaq (Isaac), his lawful heir, when the time for the succession came, Abraham was careful to dispatch all the sons of his concubines to distant places.1 They went eastward, to the east country (Bereshith (Genesis) 25:5), with of course a good supply of livestock. Midian was one of these second-class children, since his mother was a slave. The Yisraelites, therefore, could consider the Midianites near relations, although of inferior rank.

Modern ethnologists prefer to take the view that they were closely connected with the Arameans, but that the bonds of friendship between the two groups had grown steadily more tenuous with time.

The position is confusing, because the Scriptures sometimes depicts the Midianite-Kenite forces as allies of the Yisraelites (Shophtim (Judges) 1:16; 4:11,17; 1 Schmuel 15:6); sometimes it says that the People of YAHWEH waged savage and relentless war against them (Shophtim (Judges) 6:11-24; 7:1-25; 8:1-3). Then, sometimes they are said to have set up their tents in the far south of Canaan in the neighbourhood of Sinai; at others, in Jordan, east of the Dead Sea; and yet again, in the north at the great northern curve of the Euphrates. They seem to crop up everywhere.

The truth, however, is easily understood. Like the Arameans (of which the Hebrews were a branch), the Midianites were shepherd nomads of the steppe, and their clans were scattered in most places of that part of the Fertile Crescent which extends from the mountains of Syria to the Dead Sea.

Each of these groups developed in its own way, as the result of alliances, of the mingling of blood and the influence of alien beliefs. These pastoral groups remained nominally Midianite, but in their social and belief structure they underwent significant alterations. That is why, during Yisrael’s troubled history, it came into opposition with Midianite encampments in some places and collaborated with them closely in others.

After considerable argument, orientalists now agree that the geographical position of Midian is on the east of the gulf of Aqaba, one of the two narrow branches of the Red Sea which enclose the Sinai peninsular.

It is relevant to mention here the two main sources of the wealth of this region: first, the pastureland on the hillsides and in the valleys where irrigation is easy; and secondly, some amount of silver, and especially of copper ore, and a little farther south, even of gold. These ores could be extracted without difficulty. This explains why the Midianite tribes were early described as both shepherds and smiths. They were given the special name of Kenites.

MOSHEH FLEES TO THE COUNTRY OF MIDIAN

1 See preceding volume in the series, Abraham, Loved by YAHWEH.

Mosheh’ only solution was in choosing Midian as a refuge

Like all totalitarian states Egypt was equipped with a powerful police system. After the murder which he had just committed, Mosheh was obliged to flee. What direction should he take? Would it be west of the Delta, into Canaan? Decidedly not, for had he gone to the land of his ancestors, he would have had to cross a frontier bristling with Egyptian fortresses, patrols and sentries. Would it be eastward, into Libya? There, among Egypt’s enemies, a refugee would certainly have been welcome. But in order to reach it, the roads across the plains of the Delta would have had to be used, and these would be crowded with troops. In addition, these roads were closely watched. Should he, then, go up the Nile valley? That would have meant certain death.

There was indeed only one solution: the steppe of Sinai or, still better, the shores of the Red Sea. There, Mosheh might well come across a pastoral tribe of his own people or one related to it. In this region, on the coast of the gulf of Aqaba, Egypt’s power was not felt; the Rameses dynasty had no interest in these remote and deprived regions; its objective was Palestine and Syria. Gangs did occasionally extract copper and turquoises from the mines on Sinai, but the Egyptian sovereigns had little ambition to extend their dominion over the Arabian coast. The nomad tribes of this area consequently enjoyed complete independence. Here, and here alone, could the fugitive find safety.

The land of Midian was also on the caravan route linking the Euphrates by way of the Fertile Crescent, with the coasts of Arabia on the littoral of the Red Sea, and even farther south, by ship to Ethiopia. Along these routes used by merchants, news traveled quickly. From this observation post, Mosheh would be able to take note of possible future changes in Egypt.

‘Mosheh made for the land of Midian. And he sat down beside a well’ (Shemoth (Exodus) 2:15)

In the East at that time, when a stranger came to a place where he had neither friends or relations, he would go to the gate, if it was a city, or to the well, if it was a rural area. His attitude showed his need; he was looking for a kindly person who would speak to him and ask him to his house or his tent. It was the only course for a lonely man to follow, and, especially, the only way to become a member of a new community.

There are many attractive and picturesque accounts of scenes around a well, and the one involving Mosheh is an example of this tradition. Some shepherdesses with their flocks came together to the well and began to fill the troughs for their sheep to drink. They were followed by some young shepherds who started to drive the women away in order to take their place. Mosheh came to their defense, drove off the shepherds, and watered the sheep himself. When the shepherdesses reached their father’s camp, he was surprised at their coming home so soon. They told him what had happened. ‘Why did you leave the man there? Ask him to eat with us’ (Shemoth (Exodus) 2:20), the chieftain replied. It was in this manner that Mosheh found his way into the tents of Jethro, the patriarch of Midian.

Back Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Index Next

Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Founders of the Nation Scripture History Through the Ages