Rameses II: plunged Yisrael into an agony of despair

Yisrael's executioner was an Egyptian monarch

The Scripture records a number of typical details about the persecution. The victims were Abraham’s descendants; their executioner was an Egyptian monarch. The Scriptural writer, in this case, speaks simply of ‘Pharaoh’ with a capital letter, and gives no other indication of the ruler’s name.

Modern scholarship has tried to ascertain exactly which of the pharaohs was reigning when these events occurred. Today, after much hesitation and discussion among specialists, it is possible to determine the period. This sombre page of history was written in the reign of Rameses II. The conclusions of modern archaeologists who have carried out lengthy and minute excavations in that part of the land of Goshen which borders on the Wadi Tumilat have made this quite certain.

Rameses II reigned for sixty-seven years (1290-1224). This pharaoh whose mummy can be seen in the Cairo museum died at eighty-three, crowned with glory and honour. There, in his sarcophagus, we see him as he was in his last years; a wrinkled man of great age; bald, apart from a few white hairs on the nape of the neck and temples; bushy eyebrows; a finely proportioned aquiline nose; high cheek-bones; and a protruding upper lip. Radiologists have ascertained by x-rays that his teeth are in perfect condition. Even in death and lying within his coffin, his expression remains proud, majestic and imposing.

Historians consider that he was a military and diplomatic genius of the first rank. In addition, this tireless builder was an architect with a mania, and it was this that explains the fact that he plunged Yisrael into an agony of despair. It was his building craze that stimulated the spiritual awakening of Yisrael, the vocation of Mosheh, the Exodus and the return of the Hebrews to Canaan, the Promised Land.

In winter, Rameses resided at Thebes on the upper Nile. There, he began by enlarging considerably the temple of Karnak. Then he started the enormous construction known today as the Ramesseum. The most extraordinary temple of his reign is certainly that of Abu Simbel in upper Nubia with its facade nearly ninety feet wide, cut out of the rock-face itself. But his favourite residence seems to have been the Delta, where the nineteenth dynasty originated.

Along the frontier of the land of Goshen he ordered the erection -- or the restoration -- of a series of fortresses, a kind of Maginot line, intended to hold back a possible Asiatic attack, this time from the Hittites. On the ruins of the former capital of the Hyksos (the city was called the Hat-Varit; the Greeks later changed the name to Avaris), Rameses constructed the northern capital of his empire, and inevitably he bestowed his own name upon it, adding boastful epithets: Pi-Rameses aa nekthu -- the House of Rameses, great through victory. The Scriptures calls the city more simply Rameses (Shemoth (Exodus) 1:11).

In this same region of the Delta, and more precisely in the centre of the Wadi Tumilat, Rameses laid the foundations of Per-Aton (the House of Aton), in honour of Aton, the sun god of Heliopolis. The Scripture calls this city Pithom (Shemoth (Exodus) 1:11).

Thus the Yisraelite encampments were steadily surrounded by military establishments as a result of the activities of Rameses II. Four centuries before these events (c. 1600) the first Hebrew shepherds (called: ‘Yoseph’s brethren’) had set up their tents in this corner of the Delta; it was then an isolated place and they had scarcely any contact with the natives of the Nile valley. But in the time of Rameses they found themselves in the immediate neighborhood of the newly-built Egyptian cities; they met the soldiers of the frontier garrisons almost daily; and they lived close to the magnificent sanctuaries raised to the glory of the countless Egyptian gods. From this unforeseen situation sprang the drama of Yisrael’s enslavement and threatened destruction through the imposition of forced labour.

Forced labour in Egypt to perpetuate the name and to proclaim the glory of the pharaoh

Throughout the ancient East, civilian workers were summoned for a period (and of course without pay) to carry out State projects that today would be called public works.

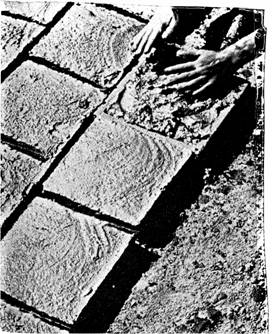

We are particularly well informed about this institution in Egypt, because in the tombs of the Nile valley many wall paintings record, in striking detail, the methods of work of the teams employed in building the palaces, temples, royal cities, the pyramids and the mastabas. The artist depicts long lines of peasants, usually impressed for a period of three months, working on some project. We see them on their way to the river to collect sand and clay which had to be carried in baskets to the building site. The mixture of earth, water and chopped straw was then trodden under foot, and the resulting crude mixture was poured into wooden moulds and exposed side by side, in huge squares, to the fierce sun. This was done in order to obtain what was called the ‘raw brick’. Then followed the removal from the moulds, an even more taxing operation. Lastly the materials had to be taken to the top of scaffolding at a dizzy height where the masons worked in gangs. There was also work at the ovens; here the bricks were baked over a wood fire; the men worked in the stifling heat of the furnace. Other and equally painful scenes are depicted on these walls: teams of men harnessed together like beasts of burden, dragging enormous blocks of stone on wooden rollers, or colossal statues for the palaces or temples in process of erection. These journeys sometimes extended to many miles; for these blocks, ready shaped or carved, came in barges from distant quarries in the south along the waterways of the Nile and its canals.

Most of the pharaohs were eager to raise buildings meant to perpetuate their name and to proclaim their glory; the architects were obliged to observe the strict timetable given to them, so that the work had to be done very rapidly indeed. The death-rate in these groups of workers must therefore have been high. They were confined in a narrow space, without hygiene, underfed, and compelled to pursue their task without stopping, while the pitiless sun beat down.

Accordingly they put slave-drivers over the Yisraelites to wear them down under heavy loads. In this way they built the store-cities of Pitho, and Rameses ...The Egyptians forced the sons of Yisrael into slavery, and made their lives unbearable with hard labour, work with clay and with brick. ..

Shemoth (Exodus) 1:11-14

Methodical persecution, directed specifically against the worshippers of YAHWEH, as an attempt at systematic destruction

The bene-Yisrael of the Delta area had, in their turn, to accept this terrible exaction, but they do not seem to have understood the real reasons for it. The masters of the Egyptian projects had to solve a labour problem in the traditional way. But the Scriptures gives a racial explanation for the forced labour of the Semitic shepherds: it considers that the labour to which Abraham’s descendants were subjected was a methodical persecution, directed specifically against the worshippers of YAHWEH, as an attempt at systematic destruction.

In the beginning of Shemoth (Exodus) we read that the Pharaoh said to his people: ‘Look, these people the sons of Yisrael have become so numerous and strong that they are a threat to us. We must be prudent and take steps against their increasing any further, or if war should break out they might add to the number of our enemies. They might take arms against us.’ Accordingly they put slave-drivers over the Yisraelites to wear them down under heavy loads. In this way they built the store-cities of Pithom and Rameses. In the end, realizing that the vital strength of Yisrael was not to be destroyed, the Egyptian monarch gave the order: ‘Throw all the boys born to the Hebrews into the River (the Nile), but let all the girls live’ (Shemoth (Exodus) 1: 9-22).

We have reached the time when the incursions of the Peoples of the Sea began; it was then that these formidable pirates started their attacks on the Delta. With a semblance of justification, the Pharaohs may have feared that the Yisraelites in the land of Goshen might one day make common cause with the invaders. They may, in fact, have thought that the sons of Yacob might constitute a fifth column.

In addition, the Hebrews had, like all nomadic shepherds, a proud and tempestuous character. These men who lived in tents only recognized as their leader the patriarch of their clan. With them freedom stood first, and for thousands of years it had been their custom to strike camp when they so decided and set it up again where they chose.

The time came, however, when the Hebrews found themselves numbered like cattle at the hands of Egyptian scribes. At dawn the foremen of the works, armed with whips, arrived at the tents to obtain delivery of the men to be taken to the construction yards. There they were set to work; some to put the ‘baked bricks’ into moulds; others, the sturdier ones, had to take their places in the human team that dragged the blocks of stone or the statues. Shouts of command punctuated the journey and the stick was generously applied.

Yisrael, the nomad of the steppe, could not accept this treatment. For them, in the words of the writer of this part of Shemoth (Exodus), Egypt became ‘the House of Slavery’. Murmurs of revolt were heard among the sons of Yacob who, being Asiatics, had in any case scant sympathy for the people of the Nile valley. The Egyptians, for their part, had always called these foreigners from the east, ‘the plague’ or ‘the leprosy’ of Asia. If the Hebrews objected to forced labour then they must be treated with even greater severity. Each side became resolute and hardened in its point of view. Each provoked the other. But the combat was unequal.

Repression soon became merciless. In some parts and for a period, the guardians of public order may have indulged in systematic destruction of the newly-born, to decrease the numbers of these foreigners who might possibly assist the People of the Sea in one of their attacks.

Yisrael did not yield an inch. At night, in the tents, the elders came to comfort the unfortunate; they spoke of YAHWEH, the ABBA of Abraham; they narrated the epic of the patriarchs; they constantly reminded them that the present trial would end; Yoseph had prophesied that the tribe would return to Canaan: ‘I am about to die,’ the former vizier of the Hyksos kings had said, ‘but YAHWEH will be sure to remember you kindly and take you back from this country to the land that he promised on oath to Abraham, Yitschaq (Isaac) and Yacob’ (Bereshith (Genesis) 50:24). But though they waited, prayed and hoped, years passed and their situation grew daily worse.

Suddenly, in these circumstances, Jochebed, the wife of Amram of the clan of Kehat (a subdivision of the tribe of Levi) gave birth to a son, who was later to be called Mosheh. He seemed to be just another Hebrew: in reality he was one of the most outstanding personalities of the Old Covenant, and he provided the main link between Abraham of Hebron and YAHSHUA of Nazareth.

Back Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Index Next

Mosheh and Yahshua Ben Nun Founders of the Nation Scripture History Through the Ages